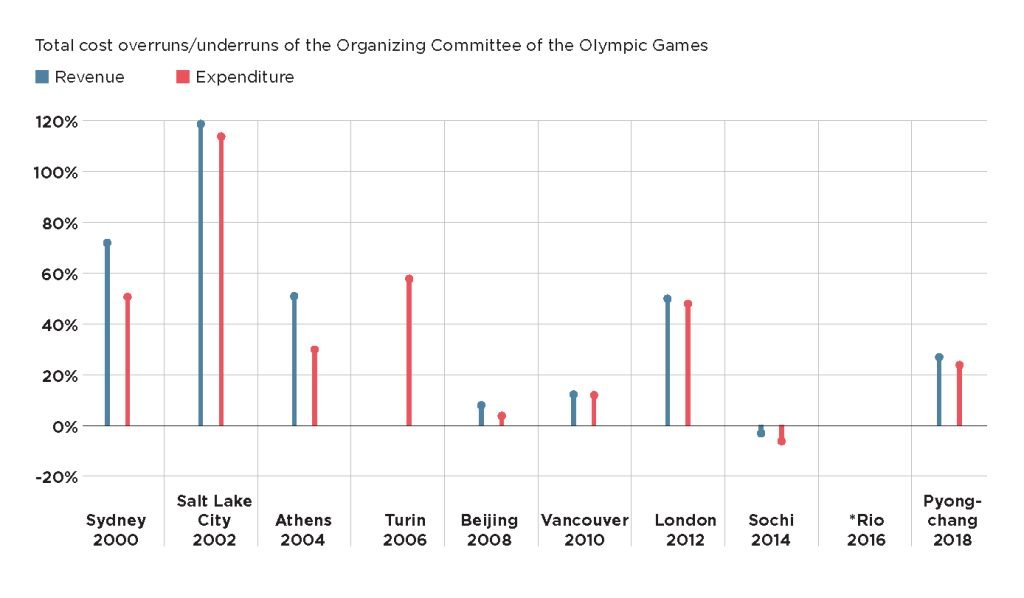

Sports economists in the U.S. like Andrew Zimbalist and Victor Mathewson argue that hosting the Olympics is a poor economic decision, causing irreversible financial strain to a country under the illusion of enriching it with monumental global value. They cite examples like Athens 2004, with a $15 billion hemorrhaged investment which brought in $168 billion in debts (an EU rescue package it is still paying) and derelict facilities. Rio De Janeiro in 2016 spent over $13 billion of taxpayers’ money and was left with piling debts of about $113 million, thousands of displaced citizens, and rising protests across the country. Adding these examples to many others in earlier years, critics assert that hosting the Olympics is simply bad business.

Other economists say that the Olympics can lead to some long-term benefits if planning is done well. “Some cities do [the Olympics] very well,” Dean Baim, professor of economics and finance at Pepperdine University, tells Worth. “If there’s a solid plan, it’d be a success. Los Angeles did it in 1984,” he says. “I would argue that Seoul and Atlanta did it too. Every facility that was built, they had a plan for it after the Olympics.”

France’s Big Bet on the 2004 Olympics

This preparedness that Baim thinks imperative and critical is what France boasts of against summer 2024—the centenary of the celebrated Paris 1924 games—when the eyes of the world will turn to it. The country believes it can change the opinions of Olympic naysayers with critical strategies that target gaining local public support and upholding sustainable practices.

It is also banking on its modest $4.4 billion budget (which may change), a gender-parity pledge in athlete and event selection, and the fact that a majority of Olympic facilities (like the 1924 “Chariots of Fire” stadium) are already in place for the July-to-August games. Like most host countries who have tried to use the Olympics to sponsor an economic boom, France projects that it will make a profit—$5-10 billion from the games alone.

Still, critics like Johan Rewilak, assistant professor of sports economics and finance at the University of South Carolina, assert that hosting will be unnecessary to France’s economic growth. It’s not a sustainable financial decision, he says, as the games are inherently destructive—echoing Andrew Zimbalist’s view.

Rewilak thinks that an already-thriving tourist destination like France does not need the Olympics to place itself on the global map. “Hosting the games may not generate the economic impact that has been previously mentioned, as Parisians may substitute spending from other areas of the local economy for sport,” says Rewilak.

He also thinks tourists will be forced to stay away from Paris for a long time for fear of being crowded or overpriced on normally affordable goods, especially as inflation is also rising (as of early 2024). “There is a sports management conference in Paris coinciding with the Olympics,” he says, “and I am choosing to stay away given how busy Paris will be!”

Accurately forecasting the economic impact of the games has remained a challenging task, but it is important to understand where the argument between optimists and skeptics is rooted and how the intricate history of the games’ economic circumstances profoundly influences present-day Olympics and ideologies about it.

There was a time when the games were simple to host, when financial losses didn’t deplete national economies, and when failed Olympics didn’t have any colossal impact on a country’s image. In the time after, though, the Olympics became so costly that financial losses had a grave national impact. What’s more, debates over the games’ economic fairness started strong arguments that could be perceived as a reflection of one’s morality.

“In the early days of the modern games, not much was spent in preparation and on facilities,” says Rod Skyles, an economist and seasoned business professional. “The Berlin games in 1936 changed that trend.”

The Economic Boom of the Early Modern Games

Pierre De Coubertin served as president of the International Olympics Committee (IOC) for the first 28 years after the games’ rebirth in 1896. In that time, Olympic disasters never resulted in any major financial losses for hosting countries. The Olympics weathered setbacks like canceled games in 1916 and World War I, and experienced gradual international recognition until Paris 1924—which changed things.

These Olympics didn’t run on any obscure political or economic windfall motivations but on the French’s desire to show their sportsmanship to the world, as well as redeem themselves from the poor work they did in Paris 1900, when they hosted the games for the first time.

It was the Olympics of many firsts, recording the largest attendance yet, being broadcast over radio, and preceding the golden era of France’s booming economy. It was also the last one for Pierre De Coubertin.

Much of Paris 1924’s success was defined by how many attendees, countries, and international delegates were present to witness and participate in it—remarkably larger than any games before. The games were especially a signifier that France’s suffering economy, fresh out of World War I, was getting back on its feet.

Increating Revenue

France did not recover the money spent on hosting and infrastructure through ticketing. But the games had converted spectators to tourists, including frequent American visitors, and eventual permanent residents who were gob smacked by the low cost of living in France. And this boosted trade. Paris had put on a good, convincing-enough show, and this naturally yielded monetary benefits. Soon after, in 1926, the country entered its Franc Poincare (named after its finance minister) zenithal era, as rates of exchange lowered, and the economy prospered.

This was a massive shift—one many bidding countries looked forward to achieving and even beating—and one that may have influenced the use of the Olympics for political propaganda years later.

The next host, Amsterdam, which had initially bid for 1924, experienced a better economic impact than Paris. It had spent $1.183 million and recovered $1.165 (about $38 million and $86 million, in today’s dollars), with a negligible loss of $18,000 ($585,000). It was also the first to introduce brand-sponsored marketing through Coca-Cola, providing American teams 1000 crates of their drink.

The Los Angeles Olympic games of 1932 were better still—superb even—and are referenced in the list of historically successful Olympiads. It’s a usual example of why some economists posit that the Olympics could be a significant financial decision. ILA powered through the limitations of the Great Depression in America with sufficient architectural, monetary, and innovative strategies. Planners considered the futuristic use of Olympic infrastructure, the safety of local communities, and the economic recession of that time—and finished with a $1 million ($32 million today) profit. It was the first Olympics not to lose money.

After the Olympics in Los Angeles, it had been established that the games were potentially a great tool in reaching peaceful international relations, especially after global conflict, scoring trade boosts, and championing a colossal increase in tourism. But the path the Olympics took after Los Angeles, politically and economically, was a sharp left.

Germany’s Budget-busting Extravaganza

Adolf Hitler was fascinated with the widespread popularity of the recent games. He saw the Olympics as a vehicle to demonstrate his racial superiority ideologies, highlight the power of Nazi Germany, and exert a propaganda coup. “1936 Berlin was driven by Hitler’s desire to show off Nazi Germany and announce to the world how special they were,” Skyles tells Worth. “Since then, many of the games have been driven by politics and not common sense or for the benefit of the people.”

Berlin 1936 cost more than $500 million in today’s dollars and was 10 times more expensive than any preceding games, putting Germany in more debt than all previous host countries combined. It was meant to be outrageously extravagant like nothing ever seen before and signal the return of Germany to the global stage after its defeat in World War I. Hitler’s unsuccessful plan plunged Germany into an economic crisis, but he had carved a new path for the Olympics.

The cost of the Olympics in the interwar era had grown naturally, but not exorbitantly, as attendance increased, participating countries multiplied, and brand awareness through the games improved. But what Hitler did in 1936 changed the economy of things forever. It created a new hope: the possibility of a global legacy. The recent Olympics era strayed far from De Coubertin’s original ideas. It gave the Olympics a fresh motto and told developing countries that the games could be their ticket to gaining global recognition. At the same time, it made industrialized countries more energized than ever.

“Each city [after Berlin] had a specific reason why it wanted to host the Olympics, and in most cases, it was to make their country appear to be a global leader. To some extent, they were successful,” Baim tells Worth.

The Modern Olympics Spending Spree

There was a 12-year break due to the Second World War after Berlin in 1936. The cost of the Olympics reverted to tens of millions of dollars for a time, a typical rate for hosting it in the interwar period. But costs soon rose with economic growth.

The Olympics after the ‘60s signified the world’s recovery from the war. It was now visible that a state could assert itself through the games. Bidding became tougher as countries scurried for the chance to show how much development they had made through the world’s center stage, the idea of exerting themselves as global leaders, and the potential economic gains (which they believed would overshadow the projected costs incurred by host cities).

Mexico, the first developing country to host the Olympics, was able to assert itself as a contemporary, cosmopolitan country through the flamboyant sports and housing architecture it built (and that remains useful). But this meant using large amounts of public funding and even massacring student protesters who sought to use the games’ global popularity to demand democracy and the elimination of authoritarianism.

The city of Rome could flaunt its high-end urban reimagination as it was the first city to get television coverage, but it left a pile of debt ($19 billion today) in its wake.

Tokyo, in 1964, went as far as spending over $10 billion in national makeovers—from stadiums to transportation infrastructure—which led to a large-scale displacement of citizens and substantial debts. Montreal in 1976 shackled the city with $1.5 billion in debt. “They ran such a huge deficit that the people of Montreal had to pay for it,” says Baim.

What to Expect for Paris 2024

There are decades of overwhelming evidence that hosting the Olympics is a costly investment, in which returns are vaguely probable, but governments remain ever hopeful.

This is hardly surprising as the payoff—when it pays—is also easy to see. The 1988 Seoul Olympics, for example, reimagined the war-linked image of South Korea and brought in investments. Barcelona became a Mediterranean gem after 1992 through modern renovations that showcased its culture and increased annual tourist visitors from 1.8m in 1990 to over 3 million in 2000. London, today, still generates money from its Olympics 12 years ago through several tournaments hosted in the Olympic stadium it built in 2012.

Many hosts have fruitlessly spent much money trying to recreate these successes, and France may be on track to do the same. It is faced with spiraling cost concerns, which made several cities like Boston withdraw their bids. This explains why bidding in general has dropped. There are also problems of rising inflation and existing security challenges, which were a big factor in Japan’s enormous financial losses after Tokyo 2021. Citizens will also leave the city during the games because they think it will be unbearable—hampering shopping, transportation, and basic day-to-day activities.

France could have chosen not to bid for hosting, and nothing would have changed. As Rewilak insists, countries like it don’t need to assert themselves as global leaders, nor do they need the Olympics to boost their economy. “The Olympics is not necessary to place Paris on the map. People go to Paris no matter what,” he says.

Mixed Signals

The country’s intent for hosting the Olympics remains somewhat vague, especially with a lot of downsides threatening its success. However, France’s evacuation of homeless people out of Paris ahead of the Olympics is an angle to consider for Baim, as he thinks it is a move to hide the city’s problems from citizens and visitors.

“The Olympics are sometimes bread and circuses to keep people’s minds off of a country’s problems,” he says. “Paris may be motivated to host the Olympics to keep Parisians and the press distracted from its number of unhoused. I think it’s the most efficient way to distract people.” Rewilak adds, “If the movement and transfer of homeless people stops—or there is movement back to Paris—after the games, it may tell the full story.”

In 2020, the IOC, an institution with a history of bribery and corruption and involvement in hospitality and doping scandals, put out a strategic roadmap agenda. The agenda seeks to reform the Olympics and the IOC. And Paris, as a host choice, may be part of it. “This isn’t a sullied country using the Olympics to improve its image. This is a sullied Olympics using a country to decontaminate itself,” Jon Werthiem, Sports Illustrated executive editor writes.

There are a few economic upsides to cling to in France’s story, though. Firstly, its eco-smart and sustainability plans to make the games pro-bike, pro-pedestrian, anti-jet, and anti-car are forward-thinking and will save costs. Secondly, Paris may be able to replicate the efficiencies of London 2012 and L.A 1984, since—like those former hosts—it doesn’t need to construct any new buildings, just rehab old ones.

France has had the ball in its court since 2017, and in a few months, it’ll play before global spectatorship. If the country has learned from mistakes of past hosts and has properly executed its pre-game strategies, it’ll be evident in the aftermath of the tournament. If not, the results would hardly be surprising.