The pandemic washed over American cities with frightening speed in early 2020, but it hasn’t receded at anything close to a uniform pace. And neither has the economic side effect of remote work—leaving business districts feeling, at best, a little lonely, at worst, zombified.

Several studies published last year have revealed one particular difference that should be grounds for measured optimism. Figures for office occupancy and downtown recovery tend to look a lot better in smaller cities than in the biggest markets—a fact often lost in the media. For instance, building-security firm Kastle’s heavily reported count of badge swipes covers only the top 10 metros, and shows only slow back-to-work progress.

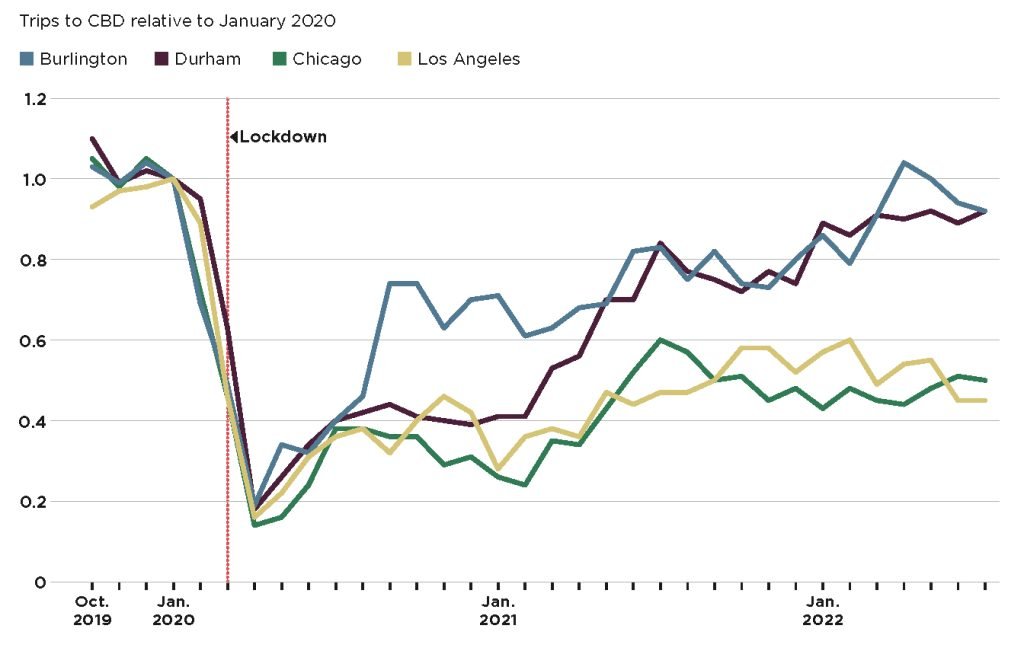

Big Back-to-Work Contrasts Between Cities

A fuller picture comes from a trio of academic researchers who analyzed smartphone-location data that business-intelligence firm SafeGraph had collected through mid 2022. Their “Remote Work and City Structure” study, published in July of 2023 by the National Bureau of Economic Research, found that while trips to central business districts remained at about 60% in the largest cities, they had, on average, returned to pre-pandemic levels in smaller cities.

The central-business-district traffic stats were especially bad for the largest cities, with Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York all under 50% CBD visits—and sometimes closer to 40%—during the time frame of this study.

Research published last July by Stanford University’s Institute for Economic Policy Research adds another dimension. In the “The Evolution of Working from Home,” researchers observed that “the work-from-home rate rises strongly with population density,” accounting for more than 40% of all paid workdays in the highest tier of urban density that three researchers surveyed.

A similar pattern surfaces in the findings of the University of Toronto’s Downtown Recovery Rankings project, also based on phone location data. Its roster of the top ten cities with the highest percentages of unique visitors to downtown (relative to a 2019 baseline) features only one city among the ten biggest in the country: Phoenix.

That list also includes some striking contrasts between bigger and smaller cities separated by under 100 miles. Milwaukee’s 86% recovery far outpaced the 61% stat for Chicago, just down Lake Michigan, and the 87% figure for Colorado Springs easily bests Denver’s 67%.

Experts point to a few factors that can explain this divergence: the types of employers and professions, the pain of commutes for them, where people live, and how much they might be willing to pay to live closer to those jobs.

Some Professions Demand More Office Time

“The difference is huge,” says Nicholas Bloom, an economics professor at Stanford and one author of the research paper. “The key driver of this is industry.”

As that report notes, work-from-home rates vary widely by industry sector. Information technology was most tolerant, with employees reporting that they worked an average of 2.55 days a week from home in the first half of 2023.

Financial and insurance came in second, with 2.28 WFH days a week reported, followed by professional and business services (for example, consulting and accounting), at 2.04 days a week.

Sectors that require hands-on, face-to-face work—hospitality and food services, transportation and warehousing, retail and manufacturing—all had employees reporting less than a day a week of remote work.

In other words, the high profile of finance in New York and information technology in San Francisco helps explain their lagging return-to-work rates. Higher shares of blue-collar work can lead to different outcomes elsewhere—like Milwaukee.

“We’ve seen about 70 new companies move in who are mostly high-tech manufacturing,” says Corey Zetts, executive director of Menomonee Valley Partners.

That neighborhood west of downtown Milwaukee has a history of manufacturing that left a legacy of pollution. But its 21st-century version is greener. Zetts noted the growing presence of the Spanish firm Ingeteam, which builds components for wind and solar energy installations and is now moving to build EV chargers in Milwaukee.

“For us, we’re really seeing things return to normal,” she says. “On any given day, the parking lots, the bike racks, look like they did in 2019.”

Remote Work’s Effects on Neighborhoods

Ferdinando Monte, a professor at Georgetown University and one author of “Remote Work and City Structure” noted that when professional tasks can be done remotely, workers’ interest in going downtown can vary based on their odds of having interesting interactions with other people at work.

“For bigger cities, a lot of the value was in personal interactions,” he says. But as more of your coworkers aren’t there, that becomes a bit of a vicious circle.

Monte added that reduced in-office populations can also drag down employment in sectors that assume in-person work, citing trends in food service work around Washington.

“Total employment in restaurants is basically at pre-pandemic levels,” he says. “But in the last year, all of the jobs that have been added have been added outside D.C. proper.”

Long Commutes Can Hinder the Return-to-Work Process

Scoop Technologies, a San Francisco developer of workforce collaboration services, maintains a Flex Index of remote-work flexibility that reveals a similar pattern between bigger and smaller markets.

The firm’s list of the 10 most flexible metro areas is based on estimates from employee surveys and publicly posted office-presence requirements covering 8,000+ companies. It leads off with San Francisco and San Jose, followed by Austin, Seattle and Boston. Meanwhile, its list of the 10 least flexible metros is all such smaller cities as Chattanooga, Wichita, and Tulsa.

Rob Sadow, Scoop co-founder and CEO, pointed to another key issue: “the underlying traffic and pain in getting back to the office.”

In other words: more stoplights and brake lights ahead mean less willingness to get in the car and turn the key (or press a “start” button).

“Atlanta tends to have a little bit lower return to office rates compared to more suburban or rural areas in Georgia and the Southeast,” Sadow says, nodding to the commuter congestion routinely clogging the ribbons of concrete that slice through the Peachtree City. “And part of that is driven by the traffic situation.”

The Stanford paper observed that firms in the information, finance, and business-services sectors are particularly prone to inflicting bad commutes on their employees because they cluster in dense urban centers.

As the report concluded: “That makes it all the more appealing to avoid the commute, thereby saving time, money, and aggravation.”

Census Bureau data about pre-pandemic commute times may also serve as a forward-looking indicator about workers’ willingness to get in a car, board a train or bus, or hop on a bike. Compare, for example, the 2019 one-way averages for New York and San Francisco—38 minutes and 35 minutes—with Milwaukee’s 24 minutes.

“Our commute times have never been very bad,” says Zetts—who also says she’d like to see the neighborhood’s pre-pandemic bus service restored.

Monte noted that larger metros should be able to offset bad driving commutes with better public transit: “Bigger cities tend to be the ones that have better transportation infrastructure.”

But many transportation services, such as the Washington area’s Metro heavy-rail system, face severe funding shortfalls in part because fewer people are working in offices and paying transit fares.

Many employers have now moved to parcel out the pain by requiring workers to show up in the office for only part of the week. Kastle’s stats now include a peak-day graph, which has been showing Tuesday as the top in-office day for hybrid workers.

“I think we will increasingly settle into two to three days at the office, two to the three at home,” Sadow says. “When three goes to four is when employees find they’re really frustrated.”

Monte says he’s seen the same, calling three days of five in an office “kind of the norm.”

Longer Commutes from Big Suburban Homes

Where and how people live can also affect how anxious they are to resume working in offices. The Stanford paper noted another reason for high work-from-home rates in information, finance and insurance, and professional and business services. They pay more, and that additional income often results in larger abodes that people may be more reluctant to leave.

As the paper’s authors write: “Higher earners typically have nicer homes with more room for a home office.”

In a guest post on Scoop’s blog last April, University of Southern California economics professor Matthew E. Kahn crunched Flex Index workplace-flexibility metrics with Zillow median home-price data and found a link. A doubling of home prices was correlated with a six percentage-point drop in onsite-only workers.

When professional tasks can be done remotely, interest in going downtown can vary based on the odds of having interesting work interactions. As more coworkers aren’t there, that

becomes a vicious circle.”

He also found that companies based in more liberal states, as measured by President Biden’s share of the popular vote in 2020, were more likely to allow WFH. Commented Kahn: “Blue State bosses of firms are more likely to be progressives who prioritize worker quality of life and want to help family-focused workers to ‘have it all’.”

That may track with all 10 of the cities at the least-flexible end of the Flex Index being in states that voted for Trump (Arkansas, Florida, Oklahoma, Kansas, Kentucky, and Tennessee), many of which also have smaller cities.

The NBER paper, meanwhile, found that the economic incentives worked the other way in cities with higher return-to-work metrics: Workers were more willing to pay extra for housing closer to their jobs.

What Monte described as “that willingness to pay to be close to office work”—more inelastic demand, in economic terms—declined for both large and small cities at the start of the pandemic. “But then it returned to where it was for these smaller cities.”

Either way, an employee’s choice of housing can constrain their future workplace choices for years to come. As Monte put it: “The people that used to live there now live outside.”

Remaking Cities for Workers

Many cities are now working to square the circle by moving away from neighborhood monocultures, with offices in a business district and housing nowhere close, in favor of mixed-use quarters that have office and residential on the same block or within blocks.

One common shortcut to that is to convert office buildings into housing—assuming their floor layouts allow a subdivision of a cubicle farm into apartments. That has the added advantage of eliminating the need to find new office tenants for those structures.

And even cities that have done well at getting people back to offices are taking this route. “We are seeing some conversions to residential,” Zetts says of downtown Milwaukee.

“We are moving increasingly to a world where people are going to live and work close to each other,” says Sadow. “The era of Microsoft creating the Redmond campus where 50,000 people work is probably past.”