It takes so little to say so much. The flick of the wrist, followed by a focused breath and a delicate yet deliberate sip, opens the door to the hidden world inside a “wee dram.” It is a character within a night’s story all in its own right. Scotch whisky has a special place in my memories.

To me, Scotch means going to the liquor store—when I was far too young to be allowed to—with my Papa, staring down the wall of single malts, deciding what we should add to the shelf. And now it’s him sitting at his desk, me in his big leather chair just beside every Friday, choosing which bottle will mark the end of our week. Was it cold or rough? Yes? Then choose an Islay. Do we have something to celebrate? Then choose a Speyside treat. Maybe it wasn’t anything special, so let’s pour something to make it so. Scotch whisky, and its homeland, carry a familial warmth for me.

Luckily, Scotland has called me twice before, and for vastly different reasons. In that tradition, for my third trip, I got to visit three distilleries under the helm of the first lady of whisky, Rachel Barrie.

Speyside’s BenRiach

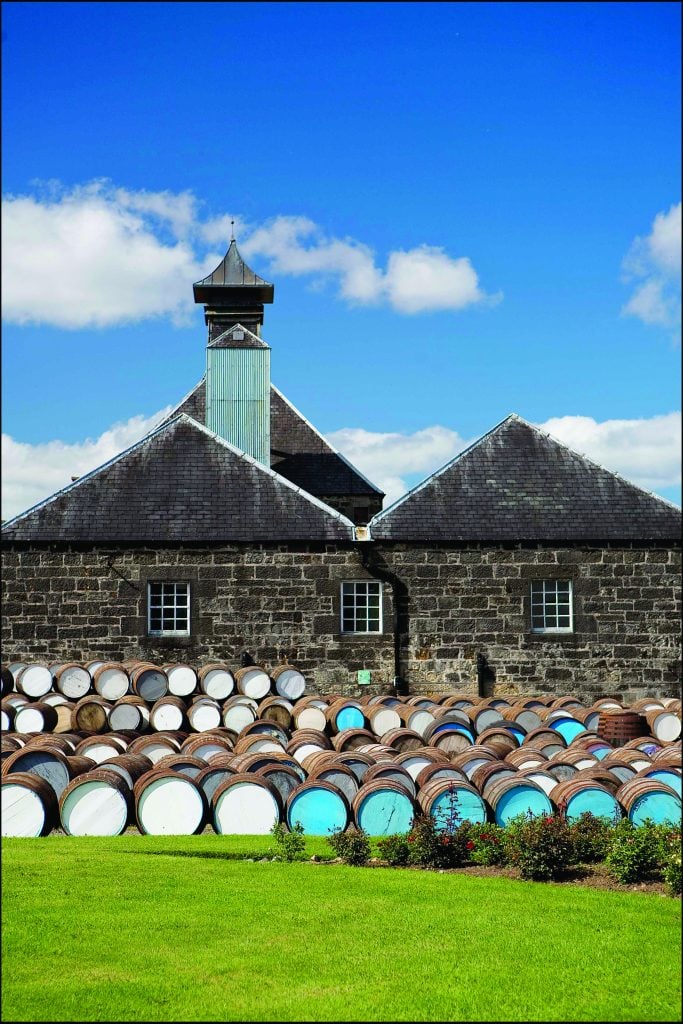

My first stop was in the highlands sub-region, Speyside, at BenRiach (Ben-REE-ick) Distillery. Speyside is the country’s largest single malt producer, responsible for more than 60% of Scotland’s output (The Whisky Exchange). Spirits from this region are known for their fruit-forward characteristics with popular notes like apple, pear, and dried fruit.

When we arrived at BenRiach, we were greeted by our guide, Stewart. From his solid-metal bald eagle belt buckle to his rebuilt rally race car and floral collared shirts, you can imagine the vast valley of stories behind him. He was engaging, passionate, and came with the unique journey of traveling from the production floor to brand ambassador. He knew the ins and outs of not only the brand but could also tell us where each whisky was in the distilling process just by the smell of the mash or the head of the wort.

BenRiach was built in 1898 by John Duff but closed two years after the Pattison Crash of 1899. The Pattison Crash, aka the Whisky Crash, was the result of whisky producers and brothers, Robert and Walter Pattison, artificially inflating the value of their property holdings and repurchased whisky inventories at elevated prices, which they had sold earlier. When the creditors came knocking, the company collapsed into liquidation due to the excessively exaggerated worth of their stocks. The Pattison Crash is still known today as one of history’s greatest cases of embezzlement and fraud, as it led to global consequences for the Scotch whisky industry.

BenRiach lay mothballed for 65 years until being bought by Seagram Distillers. Today, BenRiach is owned by Brown-Forman and BenRiach Distillery Co. and sits as a jewel in the crown of Rachel Barrie.

“I did medicine first. Wasn’t for me, too much blood and gore, and with the smell of formaldehyde—I thought nah. So, I picked chemistry because I loved creating things,” Barrie quipped with a smile, in her Scottish accent when we spoke.

When she graduated university Barrie “just happened to spot a job at Edinburgh University, on the last day it was advertised, at the Scotch Whisky Research Institute. And that is such a small institute,” she detailed, “I didn’t even know it existed. And I just said, ‘Wow, that is for me.’ Because it combined my hobby, whisky, with my passion, chemistry.”

She would spend the next three years as a whisky analyst studying flavor until moving on to production. In 2003, she became the first woman in world history to be named “Master Blender.” Fifteen years later, she became the first woman of Scotch to be inducted into Whisky Magazine’s Hall of Fame—thus why she is often referred to as “The First Lady of Whisky.”

During our conversation, I asked how she goes about her blending process and what she tries to imbue into each whisky. “It must never be boring,” she began. “It must have an identity and a richness of character and charisma like a person. They have to play a tune on your palette and tell a story with a beginning, middle, and come to an end with a rewarding and alluring finish.”

Of her three distilleries, she describes BenRiach as eclectic. “I experiment at BenRiach. It surprises, it’s got rhythm to it,” described Barrie. As a character, it’s “a lot more new world, than old world.”

Boutique Scottish Hotels

After our day at BenRiach, we went to Dowans Hotel in Aberlour. The boutique whisky hotel is situated atop a hill overlooking the beautiful highlands. Consistently, they stock over 500 single malt whiskies, including rare gems such as a 1940 Macallan and 1953 Glen Grant. Each of their 16 en-suite rooms is named after one of the neighboring distilleries. I found myself in “Tomintoul,” with an incredible valley view.

That evening, we headed to dinner at The Station Hotel for their 10-course Still & Stove Tasting Menu with coinciding whisky pairings from the distilleries. Chef Henry Lapington’s flavors were a focused showing of Scotland’s native gastronomy. Each dish was balanced, bright, thoughtful, and acid-centric. Lapington’s mutton dish stands out as it defied the typical stereotypes that come with the protein. It was light, and not the typical palette-killing, richly weighted bomb. I have tried other Scottish chefs’ tasting menus highlighting ingredients native to Scotland; none have ever painted the country’s gastronomical identity this way.

One of the most bewildering creations was the final “chocolate” dessert. Each bite is imbued with a beautifully balanced mocha quality, but there is nothing of the sort in it. Lapington figured out how to combine local ingredients such as malted barley and sunflower in such a way that it evolved the flavors into an imitation of chocolate or mocha.

The following day we headed off to both GlenDronach and Glenglassaugh Distillery.

GlenDronach in Forgue

GlenDronach (Glen-drawn-ICK) was founded in 1826 in Forgue, making it one of the first licensed distilleries in Scotland. It would remain open for the following 170 years, passing through five hands before being mothballed in 1996 by its then-owners, Allied Distillers (GlenDronach Distillery). It would resume production just six years later, and then be taken over in 2008 by BenRiach Distillery Company Ltd.

Since being appointed master blender in 2016, Barrie has worked to maintain the distillery’s legacy. “GlenDronach means ‘Valley of the Brambles,’” explained Stewart. Thus, Barrie has made a point to maintain a rich vein of dark fruit throughout its whiskies. “It’s very robust and solid. It’s got a real weight to it. But it also has this beautiful fruitness to it.”

Wherever you are, you’re going to be transported,” quipped Barrie.

“I love people in the Midwest,

who are nowhere near the ocean when they nose Sandend and go ‘Ah, reminds me

of the sea.’”

Currently, Barrie is increasing the use of Pedro Ximénez sherry casks. “GlenDronach works well with sherry casks. I’m dialing up the use of Pedro Ximénez casks, which are like the ‘king of sherry,’” Barrie detailed. The choice to use predominantly Pedro Ximénez casks for GlenDronach’s Cask Strength Batch 12 has paid off, winning tenth place in Whisky Advocate’s top world whiskies of 2023. But that wasn’t her crowning achievement of the past year.

In December, Barrie was awarded “World Whisky of the Year” for Glenglassaugh’s Sandend from Whisky Advocate. She is proud to see how her “sleeping giant is now up there with the industry giants.”

Portsoy’s Glenglassaugh

Glenglassaugh (Glen-GLASS-uh) in Portsoy, on Sandend Bay, was built in 1875, brushing up against the edge of Sanded Bay, surrounded by a valley of yellow gorse flowers. “You couldn’t get much closer to sea without being in it,” Barrie describes. It would be open and shut time after time, with its most recent shuttering in 1985. The distillery would lay dormant until Stuart Grant, former distillery manager at William Grant & Sons, came in November 2008 with financiers to “buy back the name and all the casks under it still in storage going back to 1963,” Stewart explained. BenRiach Distillery Co. bought Glenglassaugh in 2013, where it has now stood alongside BenRiach and GlenDronach for over 10 years.

If you pick up any bottle of Glenglassaugh, you’ll find the words “Shaped by Land & Sea” on the bottle. As we walked with Stewart, he explained that “the minerality of the water is four times higher here than at any neighboring distillery, with 220 mineral parts/million.” This is because the Glassaugh spring filters through a bedrock of lime.

The air of Glenglaussaugh also plays a crucial role. “The wooden washbacks take in the influence of the micro yeast, the microflora, in the air coming off the surf during fermentation,” detailed Barrie. “And that affects the whisky, giving it this incredibly distinctive umami flavor.”

The Sandend single-malt is “a blend of past, present, and future,” explained Barrie. “It’s the sense of place. As a child, I grew up learning to surf in the bay, smelling the coconut of the gorse flower. And then would go and enjoy the sweetness of a tropical fruit drizzle on my vanilla ice cream from the little ice cream shop right in town. I always remembered that taste.”

It should then come as no surprise that if you had to break down the whisky into its main characteristics, it would be coconut, sea salt, vanilla, and a boatload of mouth-watering minerality. “First-fill bourbon casks work so well because they bring out the vanilla and the coconut of the yellow gorse flowers,” explained Barrie. “Then the Manzanilla casks dial up the sweetness and sea salt.”

One brisk morning, Stewart lead a walk down the gorse field onto the bay. He handed me a bunch of the flowers to understand their unique coconut scent. As the morning sun shined on low tide, he took out a bottle of Sanded, had us take a deep breath of the surf and gorse, and nose the whisky. We were standing in Rachel Barrie’s childhood memory.

“Wherever you are, you’re going to be transported,” quipped Barrie. “I love people in the Midwest, who are nowhere near the ocean when they nose Sandend and go ‘Ah, reminds me of the sea.’”