Back in the Birdland heyday, when Charlie and Ella and Stan and Art packed the joint and made a sound for the ages, the inimitable emcee Pee Wee Marquette was known to introduce Thelonious Monk with one of history’s most brilliant mispronunciations: “The Onliest.”

Witnessing David Virelles at the keys sends one searching for a similar malapropism. However you rank yourself on a hepcat scale, it’s likely you have never seen a human do such things to a piano.

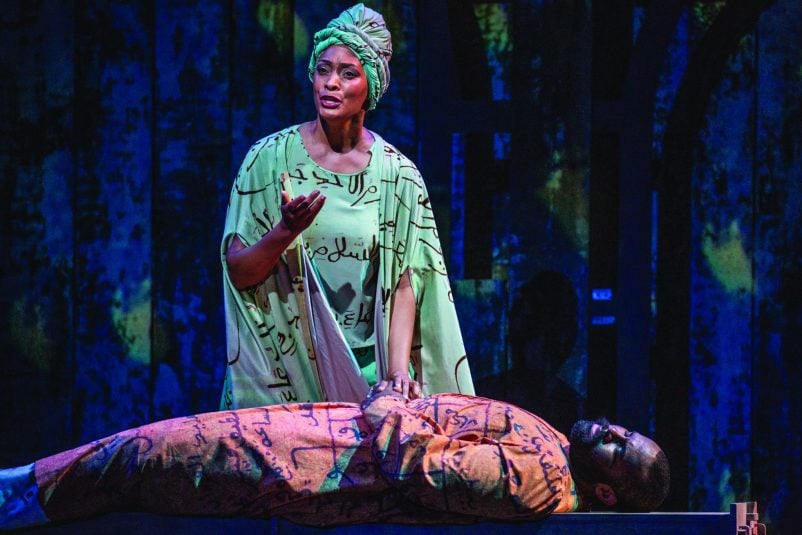

Virelles in Zurich

To comprehend a Virelles performance is to require a new poetic vocabulary, a language custom-made for his fiery athleticism and astonishing precision. Mentioning his Cuban heritage will help. Hat-tipping his tutelage at the feet of Jane Bennett and Henry Threadgill and Chris Potter and Steve Coleman gets you close. But precedence and categorization will not get you there. One must see Virelles to stand appropriately agape at his talent.

On a recent winter’s night in Zurich, just as the dominant were descending from Davos, 150 souls braved the winter rain to huddle in a moody club in the city’s industrial district. Virelles emerged humbly, ostensibly there for an evening in promotion of his new album “Carta,” an exuberant blend of Afro-Cubano sounds and avant-garde experimentations. Attendees were party to a series of beautiful violations.

Keyboard Athleticism

Here was Virelles grasping greedily at the keys, pushing, pulling, and rolling the black and whites, melting hardwood and ivorite beneath his blistering fingers. Here he was, a masseuse maneuvering across a muscled back, pushing the tension toward the edge and dragging it to center again. He plays with his elbows, his knuckles, his wrists. With the hair on his forearm? One wouldn’t be surprised.

Then suddenly a shift: He is a child pecking playfully at a toy keyboard. Then: a viper striking with the left hand, landing the bite. Then: a woodpecker, impossibly quick and needle-nosed, penetrating the skin of the surrendered instrument. No, his hands are a pair of ragged claws, scuttling across the floor of roiling seas.

He is insistent, obsessed, pounding, and then not touching anything but air—his hands suspended above the keys, sound somehow emitting from a machine now trained to read his mind. At climax, he breaks the wall, keeping his left hand striding, while the right reaches into the piano itself, fingers grazing unhammered strings.

Virelles was drenched with sweat, and the sets were short. Just as well, as the rest of us were out of metaphors anyway. The crowd began trickling out, all smiles and headshakes and gestures of astonishment. Virelles was heading back to New York, his able allies of Eric McPherson on percussion and Ben Street on bass with him, having completed a short run of shows in Paris and Geneva. Some of his students were in attendance, proud of their proximity to the preternatural, whose extreme control masquerades as chaos, whose elegance becomes indistinguishable from brute force, whose manipulation of a grand appears as gentleness.

It is a kind of mirage, a form of magic. Pee Wee might call it a Virellusion.

This review will appear in the Spring 2024 issue of Worth magazine as part of the article “Symphonies of Mastery.”