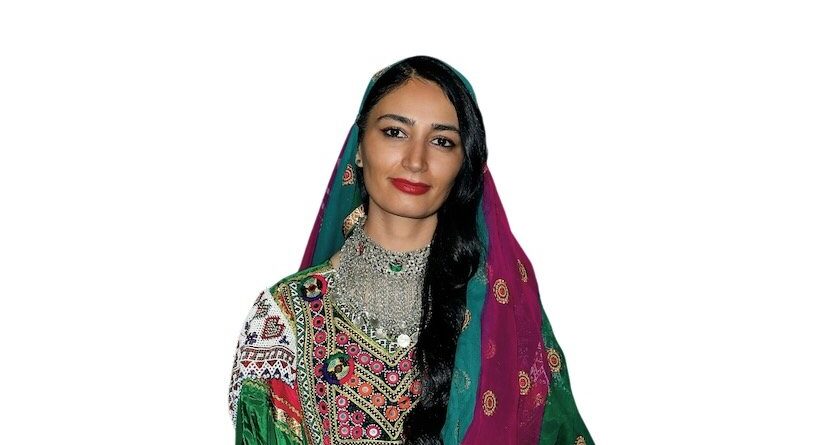

M.T. Connolly has dedicated her life to combating elder abuse. A former lawyer at the Department of Justice, she has authored a recent book, The Measure of Our Age, which investigates the state of elder care, and lack of care, in our society.

Connolly takes us through her transformative journey from addressing legal aspects of elder justice to deeply exploring the structural challenges in elder care. She highlights the changing dynamics of elder circumstances over generations, the alarming prevalence of elder abuse, and the stark reality of age segregation in our society.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you become sensitive to the issue of elder abuse?

At the Department of Justice, we launched something that we called the Nurse Initiative, and then changed the name to the Elder Justice Initiative. It focused on problems in nursing homes, abuse and neglect, and also fraud.

When I learned about the issue and dug into it, I understood it wasn’t a new problem at all. It has been going on for a very long time and is related to all sorts of structural issues. And I initially thought, look to the law for answers.

We prosecuted some nursing home chains, and we looked at how we might tweak the law. Then I went over to the Senate and worked with them on something called the “Elder Justice Act” (passed in 2010). Although we made some progress, they were not silver bullets.

So that’s what led me to write the book, because I wanted to understand at a deeper level what was going on. Why is it that as a society, we tolerate seriously substandard care for some of the most vulnerable citizens? And unlike other issues that divide us, we are all aging. It doesn’t matter who you are, where you are, your race, ethnicity, political affiliation, or geography, we’re all moving through time together. We’re all older people in training—if we’re not there already. So I want to attend at a deeper level to what was going on.

“The models we have for aging are largely either isolation or age segregation. There’s a loss when we don’t have intergenerational contact. It impoverishes our social environment.”

How has the elder care problem, the elder circumstance, changed over the generations?

There are several changes. One is that we’re really, as a society, very segregated by age now. And the models that we have for aging are largely either isolation or age segregation. There’s a loss when we don’t have more intergenerational contact because it impoverishes our social environment and our imagination. And I think that’s an important if sometimes invisible loss. Another thing is that, as a society, we’re living longer. In 1900, we lived an average of 48 years as Americans, and by 2000, and actually still today, we live an average of 78 years. That’s a lot of lengthening of life.

But the healthy life expectancy is 66. And it’s lower for people of color, people who don’t have good healthcare, who are experiencing poverty, or who don’t have an education. About three-quarters of people 85 and older have some sort of functional disability. That means a lot more people need care today than ever before. In a sense, we have this victory of longevity, but we’ve done less well at the quality of care.

What is the abuse situation? How serious is it? How common is it?

Alas, it’s much more common than people want to contemplate. About one in 10 people 60 and older are abused, exploited, or neglected. That can take a lot of different forms. Probably the most common one is financial exploitation.

Another problem that we underestimate is the harm of verbal abuse. There’s a lot of ageism in society. I’m not talking about just an offhand comment here or there, but screaming and yelling. That can be very detrimental to people.

Lastly, neglect. In facilities it is very common and very serious. Many, many care facilities are understaffed, and staffing is the most critical factor in good care. And people can be neglected at home, as well.

So there’s a lot to be concerned about, but nobody wants to think about it or read about it. My book is to help people understand, what are some of the challenges that are out there, and what are some ways that we can think about protecting ourselves better.

We have these tens of millions of baby boomers hitting retirement age now. And we all think about our life expectancy and all that we’re doing to make sure we live longer and healthier lives.

It’s very appealing to think you’re going to be healthy, healthy, healthy, healthy, and then boom, you die. And no problem. It’s another one of the reasons I wrote the book, because if we pay attention,

There are no silver bullets, obviously, but we can improve our odds by taking certain steps and going into it more knowledgeably, planning better, thinking about who we trust, who we want to make sure we stay in touch with.

And how we plan financially, in terms of staying connected to other people, and what kind of activity we want to fill our days with.

I think we need to not think of caregiving as a burden. That oftentimes it’s an opportunity, it’s a calling, it’s their chance to say thank you and give back.

I totally agree with that, as long as it doesn’t tip over into being too much. Because also, as a society, we’re really not helping caregivers. Sometimes it’s a really beautiful calling. And other times, people are running the equivalent of a pop-up intensive care unit in their living rooms while they’re trying to educate their kids or help their kids go to school.

And so I think we need to honor the work that is part of caregiving, whether it’s child care or elder care, or care for people with disabilities, or just making sure we stay in touch. And part of that is doing a much better job in caring for caregivers, in providing them training and resources and flexibility in terms of time at work.

Just acknowledging the role of the caregiver would mean a lot to a lot of people who probably don’t get recognized as much as they should.

I agree. But also saying, ”What do you need? What can I do to help?” That’s a really important part, too, because a lot of people go into it by default because of geography, proximity, or they’re not the person with a “complicated work schedule,” even though they’re doing very real and very important work. And so sometimes the entire burden, or the disproportionate quantity of the work, falls on one person. And then that’s just the default, and it becomes invisible in its own way.

And so I think also saying, ”What can we do—I do—to help?” Maybe that’s fighting with insurance companies or arranging for somebody else to come in or figure out a doctor’s appointment. There’s certainly enough work to go around. So I think it needs to be a team sport.