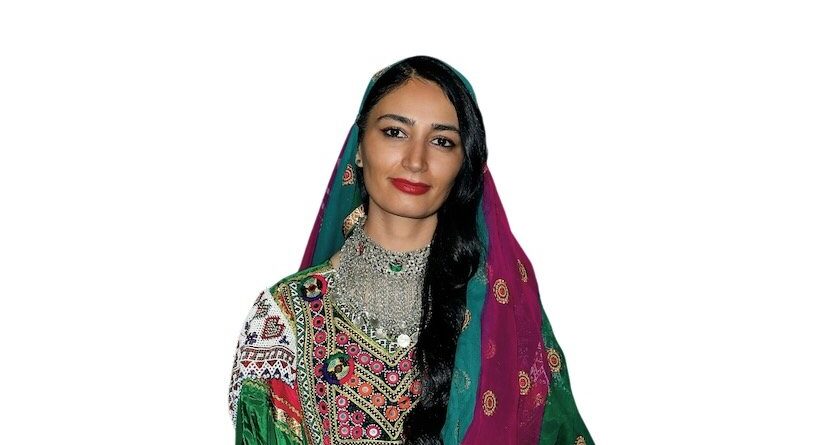

Dayana and her family crouched in the 5 a.m. darkness, the desert air hot around her even at this early hour. When they moved, they did so quickly, tugging their children as fast as they could, darting between trees and scrub. When you reach the barrier, the human smugglers said, stay put and wait to be picked up by border patrol.

“We waited there,” says Dayana—who requested to be referred to by her first name only. “At about 6 o’clock in the morning, I think, the immigration cars arrived, and they picked us up.”

A few days earlier, she and her husband fled her native Bogotá, Colombia. His work as a community activist had attracted the attention of criminal gangs who threatened their lives. So, they flew to Mexico City as soon as they could and took a bus to Mexicali, where they met the smugglers.

They left so quickly that they couldn’t even say goodbye to their extended families, she says, her eyes brimming with tears.

“Here in the United States, we have no family,” she says. “We are the four of us against the world, so to speak. So, I was very afraid to come here with nothing.”

At the immigration detention center, she says a worker from SAMU First Response, a humanitarian organization that helps migrants with immediate needs when they arrive, told her they should go to New York City.

Cost but Possible Benefits of Migrants

Dayana, who spoke with me in Spanish from New York City via Zoom through a translator, is one of the 170,700 migrants and asylum seekers who, as of January, have arrived in New York over the past two years, testing the patience and straining the resources of the city most associated with immigrants. Mayor Eric Adams, who has managed to anger almost everyone over his handling of this crisis, says the city has spent $2.4 billion since July 2022 and that if the current influx of migrants continues, they will cost a total of $10 billion by the summer of 2025, which he says will “destroy” New York City. He has pleaded for more financial help from Albany and Washington, to little avail.

But while the initial cost is giving city and state leaders a bad case of sticker shock, immigration advocates say the money should be seen as an investment.

“Immigration historically—in fact, I would say always—has been seen as a net benefit of the country,” says Muzaffar Chishti, senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank that studies U.S. immigration policy. “And that’s because they bring all the gains … They contribute to the labor [market], and they contribute to the tax base even when they’re working illegally because employers still deduct [taxes] from their paycheck. And they are eligible for no benefits. So, there’s a net gain, fiscally speaking.”

This time, it was different. Thanks to a legal right to shelter in New York City and a delay in work permits for asylum seekers like Dayana, the city and the state have been forced to shoulder the expensive burden of housing and feeding the tens of thousands of migrants who have come through the city’s systems since Spring 2022. (A 1981 consent decree mandates the city offer a bed and basic services to any homeless person who asks for them.) It’s been all cost and less gain.

But data show that once migrants and asylum seekers are settled into their new lives, they quickly begin earning wages, paying taxes, starting businesses, and reinvigorating neighborhoods. It’s just a matter of how long before these benefits manifest.

Adams’s office declined requests to comment on this story and referred me to transcripts of his media appearances and press conferences.

A Global Migration Movement

The wave of migrants arriving in New York City is part of a global phenomenon. Some 110 million people around the world have fled their homes as of mid-2023, and a third—36.4 million—are refugees, according to the American Immigration Council. This non-profit advocates for greater protections for immigrants. There are legal distinctions between migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees because responsibility for the different groups lies with various state and federal agencies.

Refugees flee their countries because of fear of persecution or human rights violations. Under the UN’s 1951 Refugee Convention, they have a right to international protection, and the responsibility for admitting and resettling refugees lies mainly with national governments. They also have the right to work, education, and access to public services.

Asylum seekers like Dayana have fled their countries for fear of persecution but have yet to be granted refugee status by the country where they’ve applied. Most of the migrants coming to New York City are asylum seekers rather than refugees. While adjudicating the asylum claims falls under the federal government’s authority, housing and feeding asylum seekers usually falls on the states and cities hosting them.

While all refugees and asylum seekers are migrants, not all migrants fall into those categories. Some have left their homes seeking better work or educational opportunities, or they might be fleeing gang violence, poverty, climate change, or political unrest.

In April 2022, Texas Governor Greg Abbott sent a bus of Cubans, Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, and Colombians to Washington, D.C.— critics say as a political statement. Some continued to New York City, attracted by its reputation as a sanctuary city and unique legal obligation to shelter homeless families.

Extra-high Costs

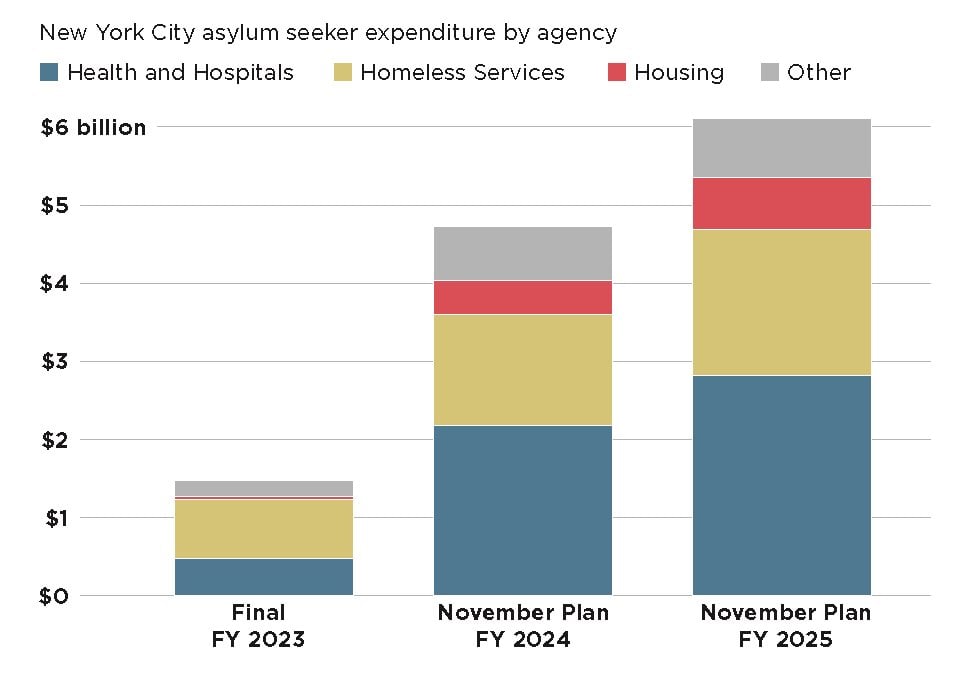

New York City initially planned to spend about $12.3 billion on migrants from 2022 to 2025, with migrant care costs, which were unplanned, making up 2.5% to 4.3% of the city’s spending in fiscal year 2023.

“That, I think, made it real,” says Chishti. “That this is not going to be sort of a nice Statue of Liberty handshake in welcoming immigrants. This has a real physical cost.”

Adams later reduced spending estimates to $10 billion in the 2024 budget, citing higher tax revenues and better fiscal management. But that left some city councilmembers and immigration advocates puzzled over what exactly, had changed.

Once migrants settle in, they begin earning wages, paying taxes, starting businesses, and reinvigorating neighborhoods. It’s just a matter of how long before benefits manifest.”

Down at the human level, the city is spending $396 a day on each migrant coming through the shelter system, according to the City Comptroller’s office. These costs include shelter, health care, Medicaid enrollment, vaccinations, school enrollment, legal orientation, and more, although a detailed breakdown of costs was not available to the comptroller as of December 2023. There are indirect costs, too, with a general strain on public services, the costs associated with integrating the new arrivals into the labor market, and the impact on communities.

Driving up the cost, the city has relied on expensive emergency contracts totaling about $5.7 billion to open more than 210 shelter sites, including 18 humanitarian relief centers, sparking accusations of waste and fraud against the Adams administration.

Take hotels. Bloomberg reported in June last year that Adams’ office agreed to pay hotels a premium—sometimes 73 percent more than a typical nightly rate—and guarantee full occupancy. The Holiday Inn in the Financial District charged $190 a night over its typical rate of $110.

On Feb. 27, the City Comptroller’s office issued a report criticizing the Adams administration for paying contracting companies millions more than necessary, with large discrepancies in the pricing of services to migrants. In one comparison, compensation for an off-site management position ranged from $58 to $201 per hour, depending on the company servicing the contract. In many cases, the report found that private contractors were paid far more than their city-employee equivalents.

In early December, comptroller Brad Lander blocked Adams’s blanket authority to issue emergency contracts for services to migrants, instead requiring agencies to get each contract individually approved.

Win NYC, the city’s largest provider of family shelter and supportive housing, reported in August 2023 that the city could save more than $3 billion a year by providing housing vouchers to migrants, regardless of immigration status.

“The City is wasting resources by failing to invest in cost-effective solutions that would help people move out of shelters and into the community,” says Joshua Goldfein, an attorney at the Legal Aid Society, the largest nonprofit legal aid provider in New York City. “They are driven by a budgetary imperative that is penny wise and pound foolish.”

No Help from Washington

Worsening the situation is that most asylum seekers cannot legally work until about six months after applying for asylum. This further strains the city’s budget; if migrants aren’t working, they’re not supporting themselves, paying rent, buying groceries, or paying taxes. Both Adams and New York Gov. Kathy Hochul have pleaded with the Biden administration to speed up work permits for migrants, but that requires Congress to act, which it has so far declined to do.

All of which leaves New York City in a bind. Republicans in Congress have used the border issue against President Joe Biden, who, in turn, is pressured by progressive Democrats who reject any new border security measures as inhumane and Trumpian. So there’s not much the city can do to stop migrants from coming and seeking services.

“New York can’t do anything about this. Immigration is a federal policy, and if no one came through Texas, then they’d just be heading for Arizona, which they’re already doing now anyway.” So says Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, which bills itself as an “independent, non-partisan, non-profit, research organization” focused on immigration.

“The migrant crisis was sparked by President Biden’s rhetoric on the campaign trail and then his actions in office,” he says. “He rolled back almost every one of President Trump’s immigration policies. … New York was bound to face this once the White House decided to dial back on enforcement of the immigration laws.”

Immigration advocates say Adams has been making the situation worse with his doomsday rhetoric. While everyone involved in the debate agrees the federal government could shoulder more of the burden on the city and state, advocates say that migrants are not to blame for New York’s budget woes.

“It gave them a scapegoat for all these other budgetary issues that were coming up at the end of the pandemic aid,” says Camille Mackler, the founder and executive director of Immigrant ARC, a coalition of more than 80 legal services providers in the city. “So, he just made all these massive cuts to schools. … [New Yorkers are] seeing it through the eyes of their kids, right? Like, all of a sudden, programs they count on are gone. And he’s blaming the migrants for it.”

Adams has since rolled back some proposed cuts.

The Positive Economic Argument

Mackler points out that the money spent so far and the billions more budgeted are down payments for the wealth migrants eventually generate once they get settled and start their lives.

“It is an investment upfront to help integrate these individuals, but it is an economic investment that will pay off,” she says. “Every statistic out there bears that out. If you look at how immigration and refugee resettlement have revitalized upstate New York, if you look at the percentage of immigrants who are new business owners or entrepreneurs, homeowners, I mean, if you look at it over time, if you invest in the issue now, it’s something that pays off.”

“I think,” she continues, referring to Adams’ complaints about costs, “from an economic standpoint, it’s been very short-sighted.”

Brad Lander, the New York City Comptroller and a progressive thorn in Adams’s side, apparently agrees and, on Jan. 4 issued a fact sheet extolling the benefits of immigration to New York.

According to the sheet, immigrants add to the economy by boosting spending and paying taxes: New York State collected $3 billion from undocumented immigrants alone in 2021. And they fill valuable jobs. Seventy percent of undocumented immigrants in New York City work in jobs considered essential.

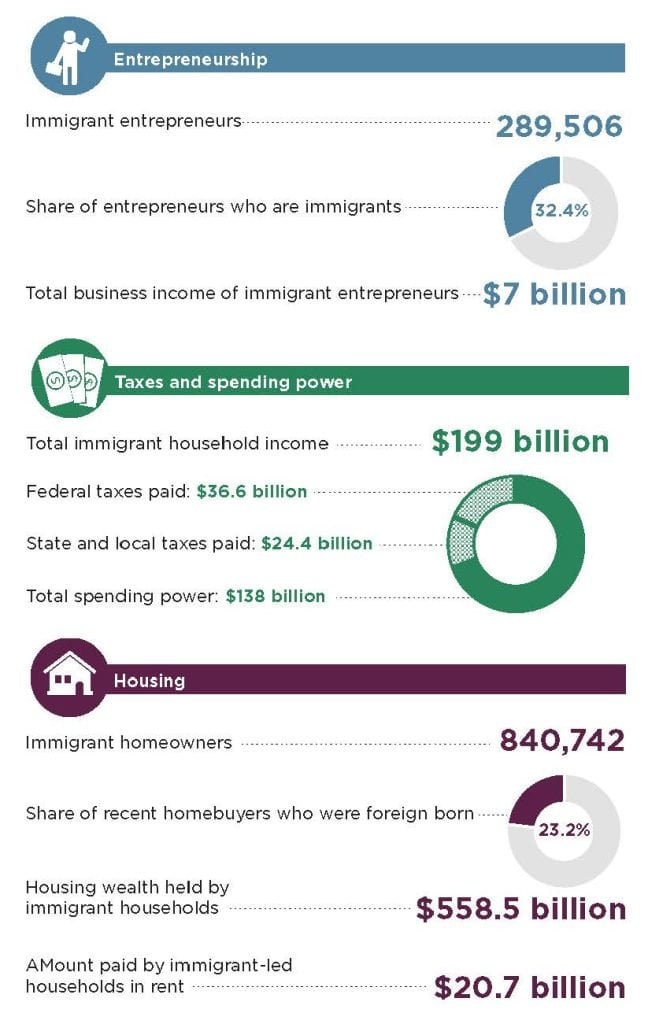

At the state level, 32.4% of entrepreneurs are immigrants, reports the American Immigration Council, generating $7 billion in business income. Immigrant households in New York paid $61 billion in local, state, and federal taxes in 2021, with an aggregate income of $199 billion.

Nationally, migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees paid $524.7 billion in total taxes in 2021, the Council reported, and had $1.4 trillion in spending power. The undocumented contingent paid $31.1 billion in taxes and had $228 billion in spending power.

“There are challenges to be sure, but political leaders can have a little confidence that in the long run, this is what makes New York the city it is and America the country we are,” says David Dyssegaard Kallick, director of the Immigration Research Initiative, a think tank that studies immigrant integration. “Our economy and culture are richer and stronger for the immigration we’ve had over the decades, and it will continue to be richer and stronger with newly arriving immigrants today.”

Building a New Life

Dayana now lives in a hotel in the Bronx with her family. Her son is learning cello in school, and she is effusive in praising the teachers and the principal there. “They have been very supportive. They have given me a lot of help with my children, with everything, she says. “The school’s principal is a person with a very big heart, really, an excellent person.”

Her husband works in construction now, and she is learning English, hopeful to put her old skills as a nurse to use somewhere, somehow.

Dayana is learning the city, the subway, her favorite bodega, just like every new New Yorker does. She keeps her head down, tries to go unnoticed. Sometimes, she gets hassled by people offended by her presence.

“They make comments like, ‘Oh, but why did you come from your country? Why didn’t you stay there? What are you doing here? Are they taking [something] away because of you? Are they taking X, Y things away from us?” She cries a little as she tells me this, the cold whipping away the tears.

But she had good news, too. On Jan. 2, she and her family received asylum, she says, 18 months after arriving in New York. She and her husband are now eligible for work permits, Social Security cards, and other federal assistance. She is still anxious.

“I am really struggling here. I fight every day for my children because I want them to be calm and happy, not to live in fear,” she says. “I know that my son, he has understood everything, and he realizes everything… [Since] his fourth birthday, he hasn’t had peace of mind and tranquility. So, as a mother, I want to give him that peace of mind.”