There are a lot of hyperbolic and crazy-sounding theories and assertions in the vast movement to counteract the inexorable march from the quick to the dead. Xprize founder Dr. Peter Diamandis thinks we may one day upload our consciousness to the cloud. As such, the 62-year-old is doing everything he can to keep his body healthy in the meantime and maybe reach “longevity escape velocity”—continuing to extend his life long enough to take advantage of ever-more life-extending methods. His business partner—motivational speaker and entrepreneur Tony Robbins—says that stem cell injections he received in Panama (because it’s illegal in the U.S.) not only repaired a torn rotator cuff but rejuvenated his entire body. Half-billionaire Bryan Johnson reportedly spends about two million dollars a year on testing, taking more than 100 drugs and supplements, and—for a time—infusing his teenage son’s blood plasma. And they are not alone. Jeff Bezos, Yuri Milner, and other tech titans are reported to have together poured about $3 billion into Altos Labs, a startup promising to reprogram human cells to their youthful state.

But the most extreme theories and practices are a veneer over a vast body of laboratory and clinical research, and even DIY biohacking, indicating it may be possible to at least slow the aging process. Could most of us live to or beyond 120 years, considered the uppermost limit of human lifespan? Some advocates, including those with university research labs, think so. Others call it bunk.

Rejuvenation efforts also promise to brighten the twilight years by allowing people to live longer and be healthier and more vigorous. Picture 80-year-olds with the body of a 60-year-old. Proponents talk about not only extending lifespan but also what they call healthspan.

“It’s this biology of aging that makes us get Alzheimer’s or cancer or heart [disease] or diabetes,” says Dr. Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. “Aging is the mother of those diseases…You deal with the mother, and you don’t have those kids.”

After speaking with a dozen experts or advocates, reading four books, parsing over 30 research papers, and absorbing popular press coverage—I know two things about the possibility of slowing or reversing aging. First, anyone can do a few cheap, simple things (like exercise) to improve their longevity prospects. Second, several new tactics, technologies, and tools might someday work.

It’s worth looking deeper at these ideas—but with a skeptical eye. That’s especially true because proponents and detractors may have a financial stake in the success or failure of new therapies. The quest for longevity is not just a matter of science but of money, personal philosophy, and personal rivalry.

Jump down this rabbit hole with me—tracing longevity science and speculation from the simple to the startling.

We’re Already Living Longer

Life extension is not a new phenomenon. Since 1800, average life expectancy has roughly doubled globally. Much of this was the statistical result falling infant mortality rates. But the ability to live longer has still grown significantly, as has quality of life in older years.

Most of these gains came from basic advances like improving nutrition and sanitation, cutting pollution, and developing vaccines. People can also vastly improve health and longevity with simple lifestyle changes—eat better, exercise more, sleep enough, spend time with friends, handle stress, and avoid nasty substances (especially cigarettes). These so-called six pillars of health are equivalent to dipping a toe into the fountain of youth.

“First and foremost is exercise,” says Diamandis. “The second thing is minimizing sugar in your diet…The third thing is getting sufficient sleep. You know, these are the basics.”

Advice on those basics forms the core of his latest book, Longevity: Your Practical Playbook. It’s a less-intense counterpart to 2022’s Life Force, his collaboration with Tony Robbins. That book includes pillar-of-health-type advice and goes deep into topics such as stem cell injections and gene therapies. (The book, whose proceeds go to charity, states: “The author and publisher specifically disclaim all responsibility for any liability, loss or risk, personal or otherwise, which is incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, of the use and application of any of the contents of this book.”)

Beyond that toe-dip of lifestyle changes, the fountain of youth gets increasingly deep, murky, and even treacherous—with possible deal-breaking side effects from losing muscle mass to developing cancer.

Trying to Define Aging

The hallmarks of aging are obvious. As Hamlet described a few, “old men have gray beards, their faces are wrinkled, their eyes [are] full of crust and gunk, and…they both lack wisdom and have weak thighs.”

But those are symptoms on the macro level. Humans are vast amalgams of cells (from 28 to 36 trillion in adults). In 2013, researchers proposed a new set of hallmarks. The list began with nine and grew to 12 in 2022. Most focus on critical mechanisms inside cells: proteins misform, DNA degrades, energy systems malfunction, nutrition suffers. Other hallmarks manifest among cells: communication breaks down, old and diseased cells poison their neighbors, tissue-renewing stem cells disappear. A few, like inflammation, range across the body.

The 12 Hallmarks of Aging

- Genomic instability: accumulated damage to protein-coding DNA and RNA.

- Telomere attrition: protective caps on DNA degrade.

- Epigenetic alterations: pattern of turning genes “on” or “off” changes.

- Loss of proteostasis: malformed proteins created in the cells.

- Disabled macroautophagy: cells lose the ability to recycle worn-out components.

- Deregulated nutrient-sensing: cells fail to regulate based on nutrient availability.

- Mitochondrial dysfunction: energy-producing cell components become abnormal.

- Cellular senescence: diseased cells excrete inflammatory substances.

- Stem cell exhaustion: reservoirs of tissue-renewing cells plummet.

- Altered intercellular communication: a dialogue breakdown has body-wide effects.

- Chronic inflammation: an over-reactive immune response.

- Dysbiosis: the balance of microbes in the gut changes.

“I think they’ve been very useful,” says Matt Kaeberlein, who ran an eponymous lab that studied aging at the University of Washington from 2006-2023. “But I think they also cause the field to become narrow and very focused, when there’s still a lot of biology we’ve never explored and don’t understand.”

Even if incomplete, the hallmarks move towards a framework for measuring aging. A person comprised of healthy cells is likely to be a healthy person. The best example of that is a baby.

Dr. Robert Hariri recounts the story of a child who had surgery in utero and showed no scars after birth. “That suggested, obviously, that in the process of building this fetus into a newborn, there’s continual, very functional renovation and renewal of the tissues to a state of optimum biology,” he says. The third author of Life Force is the CEO of a startup, Celularity, developing stem cell therapies.

But whatever may happen at the micro level has to manifest at the macro. Charles Brenner, who heads research on diabetes and cancer metabolism at City of Hope, focuses on the obvious. “If you couldn’t climb the stairs when you were a smoker, and you quit smoking, and then you were able to climb the stairs without being out of breath, that’s a convincing functional improvement,” he says.

Diamandis also wants functional proof. His 28th Xprize has raised over $100 million for awards to teams that can show, in clinical trials of 65-to-80-year-olds, significant improvement of muscle, cognitive, and immune function. (Nir Barzilai serves on the advisory board.) Over 200 teams from about 40 countries had preregistered by early February.

The Hierarchy of (Possible) Rejuvenation

Methods for extending lifespan progress from very practical to highly speculative.

They start with the six pillars (or similar prescriptions). Exercise combats aging mechanisms, including the tendency to lose skeletal muscle mass that begins as early as age 30. “Our glucose disposal depends upon our skeletal muscle mass, our quality of life, and our resistance to accidents and falling,” says Brenner. “As you degrade the ability to do glucose disposal, you tend to get fatty liver and insulin resistance and prediabetes [and] diabetes—which feeds into the increases that we’re seeing in liver cancer. And it is also linked to increased rates of cognitive impairment and central nerve degeneration.” Yep, muscle is key.

Building muscle requires a lot of protein. Layne Norton, nutrition researcher and founder of wellness company Biolayne, recommends at least 0.7 grams of protein per day for every pound of body weight. That’s a mouthful; many advocates recommend at least one gram per pound.

Many other nutrients are critical. “I’ve probably been, the last two decades of my life, vitamin D deficient, vitamin B 12 deficient, omega 3 deficient,” says Matt Kaeberlein. “There’s some low-hanging fruit…those can have a big impact on people’s healthspan.”

Even socializing helps. It boosts the “love hormone” oxytocin, which can lower heart rate, blood pressure, and levels of the stress hormone cortisol. It may also lower unhealthy blood glucose levels. “Social engagement and mental activity is really important,” says Brenner.

Techniques that further build upon the pillars get increasingly involved, uncertain, and potentially dangerous. Here’s an abbreviated hierarchy.

First come quasi-natural remedies that build upon pillars such as nutrition. They include various supplements, which may improve metabolism or other cellular functions. Another tack is limiting calories overall or fasting for chunks of the day.

Then comes the first tranche of pharmaceuticals—current medications repurposed for off-label uses. The big names are metformin—a diabetes drug—and rapamycin—which suppresses the immune system from attacking organ transplants.

Researchers, such as Kaeberlein, are also hunting for brand-new drugs aimed at specific mechanisms that may affect cellular health.

Other remedies propose injecting stem cells to rebuild tissue. These including embryonic stem cells derived from fetuses, adult cells regressed to their fetal state, and stem cells harvested from human placentas.

After incorporating another person’s cells comes rewiring your own. Not only does DNA degrade with age, but the way it’s read to provide protein-building instructions—known as epigenetics—also changes. Restoring proper epigenetics could restore youthful cells—or trigger cancer.

Quasi-Natural Remedies

Beyond essential nutrients that maintain cells, can others renew them? Among the key candidates are supplements that boost NAD, or nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. “NAD is the central catalyst of metabolism,” says Brenner. It facilitates functions, including the breakdown of glucose and the production of energy-delivery molecules in the cells’ mitochondria. It may also help repair DNA. Levels of NAD decline with age, but Brenner discovered that a vitamin, nicotinamide riboside (NR), can boost NAD levels.

Supplement Controversies

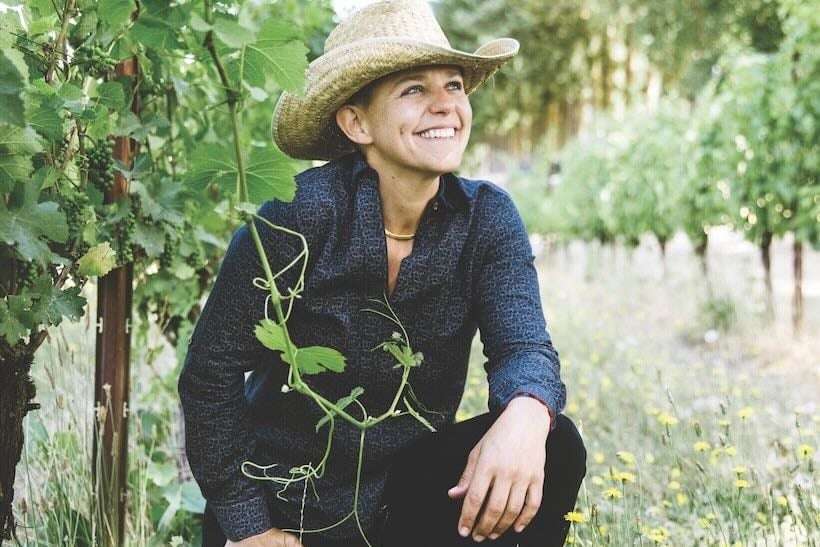

Brenner quickly discloses his financial interest: a side gig as chief scientific advisor for ChromaDex, which sells NR under the name Tru Niagen. (He’s also founder or cofounder of three other companies related to NR or aspects of NAD biology.) Other companies also sell nicotinamide riboside and another potential NAD booster, nicotinamide mononucleotide, or NMN. A prominent promoter of the latter is Harvard researcher David Sinclair.

Sinclair’s involvement goes back to a 1997 study, in which he found that NAD can help regulate a family of proteins called sirtuins, which improve epigenetic health and boost longevity in yeast. One result was the explosion of interest in resveratrol (found in red wine, and many supplements) to activate sirtuins. (Sinclair claims no financial interest in companies selling resveratrol, NR, or NMN.)

In a 2022 Twitter thread, Brenner called Sinclair’s 1997 report, “a very nice paper,” then tore into its implications, saying it doesn’t even apply to all types of yeast cells—let alone human cells. Brenner has been a strident critic of many of Sinclair’s claims.

Other supplements might help restore healthy epigenetics, says Shelley Berger, director of the Epigenetics Program at the University of Pennsylvania. “There are some very good scientists that have been involved in some of the supplements that are affecting [epigenetics],” she says. When ask for examples, Berger replies, “I’m not going to advertise anything, in particular.”

Supplements are a charged topic, with much controversy over what works and what’s snake oil—and significant tensions between researchers and retailers. “There are so many claims by so many different products,” says Diamandis, co-founder (along with Tony Robbins), of Lifeforce, which sells supplements and meds for off-label uses.

The extreme case for supplements is serial tech entrepreneur Bryan Johnson, who swallows dozens of pills. “When I look at each one of the supplements, I understand why he picked those,” says Barzilai. “In his mind, if he’s taking all of them together, they’ll be additive, or even synergistic…And he’s missing the fact that some of them are antagonistic to each other.”

Slashing Calories

The complement to absorbing more nutrients is consuming fewer calories. “There’s one intervention where you can get 50% lifespan extension in a mouse. And that’s caloric restriction. And that comes from an experiment that was done in the 1990s,” says Kaeberlein. But those conditions were extreme. Mice rations were cut by 40%. And while they lived longer on average, many experienced physical stress and immune system weakening.

Starting in 2007, a massive multi-year clinical trial called Calerie analyzed whether caloric restriction could work in humans, at humane levels (ranging from 12% to 30% cuts). A 2022 analysis of the data found that even lighter dieters showed several signs of better health, including reduced inflammation, and higher production of immune system T-cells and energy-producing mitochondria.

Another dietary option is intermittent fasting or time-restricted eating. It may or may not involve fewer calories overall, but limits when you get them to a few hours a day. A 2022 study in mice hints that such a routine could suppress genes involved in inflammation and improve protein production, among other effects.

But fasting is tough and has downsides, says former intermittent faster Diamandis. “My primary goal has been putting on muscle mass. And to do that, you need a significant amount of protein in your diet,” he says. “And you can’t absorb all of it in one sitting.” It’s one of several instances where methods intended to extend lifespan may undermine its foundation—muscle.

Off-label Medications

Much of modern pharmacy is not about discovering new drugs but new uses for those already on shelves. That’s a major antiaging trend focused on two cheap generics: metformin and rapamycin. (It’s relatively easy to find doctors to prescribe such drugs for off-label use.)

“Metformin affects all hallmarks of aging, not just glucose levels or diabetes,” says Nir Barzilai, citing his own research, among others’. “Its benefits extend to various health aspects, including immune function, and it has been shown to reduce hospitalizations and mortality from Covid-19.” Also on the list of potential benefits: combating cancer and inflammatory diseases, and improving the health of the “gut microbiome”—the mix of bacteria in the intestines.

Charles Brenner doubts all this. “Metformin is a very useful drug for type-two diabetes,” says the diabetes researcher. “But it’s not been shown to provide benefits to people without type-two diabetes.”

There’s room for disagreement, in part, from lingering mystery around metformin. Even if it does work against aging, no one can say precisely how. “If you ask five different scientists, you’ll get seven different answers,” says scientist-turned-journalist Andrew Steele, author of the book Ageless: The New Science of Getting Older Without Getting Old.

Metformin comes from goat’s rue, an herbal remedy used for centuries to treat ailments including arthritis, flu, and “excessive urination” (possibly a symptom of diabetes). “Metformin—that’s probably the last of the old-school drugs that were just tried, but we don’t really know how they work,” says Dr. Sundeep Khosla, who studies age-related effects on bone at the Mayo Clinic.

One undisputed effect is metformin’s ability to lower blood glucose levels (although how it does that is still unclear). Perhaps that is enough to impart antiaging effects. One (unproven) theory is that metformin mimics the possible age-extending effects of caloric restriction.

“That’s ridiculous! It’s not glucose dependent at all,” says Barzilai. He points to studies comparing metformin to other glucose-regulating drugs. The patients on metformin had better overall health outcomes, even though they had worse glucose control than those on other drugs. (Researchers didn’t rule out that the rival drug might somehow harm patients.)

But Barzilai acknowledges the uncertainty. “If you’re asking me, ‘But which of the hallmarks of aging is it attacking first?’ I don’t know if I can tell you,” he says, adding that the effects can also vary from organ to organ.

Adverse effects are also uncertain; but once again, muscle loss is a concern. “In fact, there are data showing that it blunts the beneficial effects of exercise in adult people,” says Brenner. That risk persuaded Diamandis to switch to berberine, a supplement that may lower blood sugar. (His company, Lifeforce, does sell metformin.)

“It’s extraordinarily safe,” says Khosla. But he adds that there is “just a very low risk” of a buildup of lactic acid in the blood, which can result in anything from sore muscles to organ failure. “I think there’s such compelling observational data, and some clinical trial data, for beneficial effects of metformin, that by all means [more research] should be pursued,” he says.

That’s what Barzilai aims to do with a clinical trial called TAME, Targeting Aging with Metformin. Such trials are challenging because they aren’t aimed at addresses a specific disease—as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration likes.

“The reason I’m doing TAME is to force the FDA to accept the concept that we can prevent a bunch of age-related diseases,” says Barzilai. “We don’t really care what disease you’re going to get. Whatever it was, we’re going to prevent it.”

If he can get the money. Two funders have dropped out, and another cut his pledge by two-thirds. But with about half the money in place, Barzilai aims to start the study this year. (He says he has no financial interests in any metformin-related work.)

Rapamycin

Like metformin, rapamycin is another drug that nature gifted without an instruction manual. Discovered in soil bacteria on Easter Island, it’s a powerful immune-suppressant for organ-transplant patients. Studies also show that it can fight cancer.

Unlike metformin, rapamycin has a clear target in cells—inhibiting an enzyme family called mTOR, the mammalian target of rapamycin. “Rapamycin…improves mitochondrial function, autophagy [recycling materials in cells], how cells deal with nutrient sensing and the utilization of nutrients,” says Yousin Suh, who researches reproduction and genetics at Columbia University. “They even control the gene expression program.”

Studies dating to 2009 seem to show rapamycin extending the lives of elderly mice. More-recent studies hint that it can slow aging in mice and rat ovaries. Suh and a team of researchers are now several months into a human clinical trial with a catchy acronym: VIBRANT, or Validating Benefits of Rapamycin for Reproductive Aging Treatment.

“The ovary ages the fastest in the human body,” says Suh. “The reproduction function declines, already in women in their 30s, with a rather drastic decline, which culminates in menopause around age 50.” Women who develop menopause later live longer and are healthier in their older years, she says—as are their brothers.

If rapamycin does slow the aging of ovaries in women, it could directly soften or delay the overall aging process, says Suh, and it might hint that rapamycin extends the healthspan for men, too.

It may also have that ever-present negative effect. “Rapamycin and rapalogs [derivatives] are inhibitors of something that helps you maintain your skeletal muscle mass,” says Charles Brenner, referring to chemical processes kicked off by exercise.

And of course, rapamycin can suppress the immune system. But Suh’s test subjects will receive a lot less rapamycin than transplant patients, and they are starting from a much healthier point. “Organ transplantation patients’ use of rapamycin gave a bad rap to rapamycin because of the particular conditions,” says Suh. Some studies show that low doses of a rapamycin derivative could even help the immune system in older people.

While formal human studies are limited, informal experiments by longevity hackers and doctors willing to prescribe to them are legion. To see if they could learn from these hackers, Kaeberlein, Suh, and other researchers set up an online survey that attracted around 300 people who took rapamycin off-label and almost 200 who had never taken it. Dosages were all over the place, and the study relied on what people claimed their health effects might be.

But the results were still interesting. Rapamycin takers overall reported less abdominal cramps and pain, muscle tightness, eye pain, depression, and anxiety. Also, those who got Covid-19 didn’t seem to get as sick or develop long Covid. One notable side effect was mouth sores—which was expected, based on other studies.

The most significant practical result of the study was helping Suh decide on safe doses for younger participants in the VIBRANT trial on ovaries. Still, she doesn’t recommend making a habit of such informal studies. “Of course, you have to do the right, randomized, double-blinded clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of the drug and on the outcome,” she says. (Suh is an advisor to longevity-focused venture capital firm LongeVC.)

Charles Brenner agrees. “I think it’s worth figuring out how to do those trials,” he says. “I’m not sure that rapamycin and metformin for the general population are very likely to provide positive results. But there certainly is a community of people that would like to see the trials done.”

Brand-New Medications

Whatever their actual effectiveness, metformin, rapamycin, and other off-the-shelf drugs are just the start. “The next phase, I think, there’s going to be much more mechanism-specific drugs,” says Khosla, “where we truly understand what the molecular or cellular target is.”

Zombie Killers

He’s starting with drugs called senolytics. “The idea is that as cells age and get DNA damaged, they increase and become cancer. But nature evolved the senescence mechanism,” says Khosla. Senescent cells are essentially zombies. They no longer grow or divide to spread their mangled DNA into cancerous growths. But they still harm the body by excreting inflammatory agents.

Senolytics attack proteins that help keep zombie cells alive. True to form, the first batch of senolytics are repurposed medications or other substances—such as the anticancer-med Dasatinib, as well as quercetin, the bitter-tasting chemical in apple peels. Khosla helped identify such substances and is testing some of them to clear senescent bone cells. (Other senolytic treatments aim to boost the immune system’s natural ability to remove senescent cells.)

“Senolytic drugs have good effects, but they also have bad effects,” says Khosla, such as the risk of bleeding. There’s another potential danger. If senescence prevents cancer, can messing with this mechanism increase the cancer risk? It’s an open question.

“I think what you want to do is basically continue to modify these drugs, so you can get the beneficial effects without these adverse effects,” says Khosla. He names an in-development medication called UBX1325, designed to clear senescent cells that cause a vision-destroying swelling of the retina. “That’s probably the closest to a drug where we know how it works, that’s actually showing some efficacy,” he says.

Casting a Wide Net

The counterpart to carefully crafting new drugs is to throw molecular spaghetti at the wall. To date, about 1100 drugs have been tested to extend lifespan. Using automated testing, Matt Kaeberlein reckons he can increase that 100-fold, with a project called the Million Molecule Challenge.

In it, petri dishes filled with tiny worms are each doused with a different chemical, and a camera equipped with computer vision records how long the worms continue moving around. If the worms in a particular dish are especially spry, the corresponding molecule becomes a candidate for further study.

“Figure out what gives us the biggest effect on lifespan, then figure out how it’s working,” says Kaeberlein. He couldn’t get funding for such a study in academia—what researchers deride as a “fishing expedition.” So he went private, co-founding Ora Biomedical to do the challenge. He’s still raising money but has started the testing. (Kaeberlein is also CEO of longevity-focused healthcare company Optispan and has equity in supplements company Novos and epigenetics startup Moonwalk Biosciences, among others.)

The for-profit aspect raises concerns about trustworthiness. “That’s why I’ve been at Mayo for 35 years, because I don’t have my own startup, because that’s not my mindset,” says Khosla. “You really have to have the fundamental biology and never overpromise.”

Brenner has financial interest in NAD-boosting products. Sinclair’s latest declaration of financial interests (from 2022) lists 43 company affiliations. Diamandis says that he has invested in more than 100 biotech and health tech companies and advises more than 30. He and Robins have written longevity advice books promoting their companies, such as Fountain Life and Lifespan. Does that compromise their objectivity? I ask Diamandis.

“I am not being objective,” he says. “I am investing in the companies that I think are the most important and exciting to move the needle forward.”

Stem Cell Injections

That brings us to the third member of the Fountain Life and Life Force (the book) trio: Dr. Robert Hariri. In 1986, Hariri published the results of an odd test—transplanting diseased blood vessels from old rats into younger ones. “I could…put it into a young animal and come back in a month. And it was indistinguishable from a young vessel,” he says. “I was setting up an opportunity for that vascular template to be repopulated by young cells.”

He then looked for other sources of young cells—and found them in the placenta that nourishes a developing baby. This medical waste is an abundant source of stem cells—which he believes can be injected into other people to repair and rebuild older bodies. (Or, if someone’s parents bank their frozen placenta with one of Hariri’s companies, they could later get injections of their own cells.)

“Every stem cell thinks it’s in a fetus,” he says. “The beauty of the fetal system is it’s in a continual state of regenerative energy, and it’s designed to basically build that newborn and retard or prohibit any events which would damage the quality of the newborn.”

Crashes in stem cell reserves, anywhere between age 20 and 40, are a hallmark of aging. Hariri envisions countering this with some cadence of stem cell replenishment treatments throughout life.

Some stem cell therapies have been going on for decades. A key example is bone marrow transplants—often given to cancer patients, either to swap out defective blood-making cells (in the case of leukemia), or to replace marrow damaged by chemotherapy.

Skepticism and Alarm

But many in the aging research community need more clarification about effectiveness and safety for antiaging purposes. “There’s very little hard evidence that they truly have clinically meaningful effects,” says Khosla. “The trials haven’t had adequate controls or adequate follow up.”

Hariri offers a personal case study. “I have two horribly torn rotator cuffs in my shoulders,” he says. “Rather than choose to have a total shoulder replacement with a prosthetic, I’ve chosen to use regenerative therapy. It’s given me benefits that I wouldn’t get from other approaches.”

Although he’s CEO of Celularity, a U.S. company developing stem cell therapy tech, Hariri had to go to Mexico and Panama for treatment, since such procedures aren’t currently allowed in the U.S. (Valued at $1.25 billion when it went public, Celularity’s market cap was about $100 million in February.)

He’s joined by fellow co-authors Robins and Diamandis in making such a trek. (Diamandis serves as director of Cellularity, which he describes as one of his major financial holdings in health tech.)

Ageless author Andrew Steele discounts anecdotal results as subject to the wishful-thinking placebo effect. “So even if you do go to one of these clinics, you get an injection of something, and you come back and feel better, that isn’t necessarily proof that what they put inside you is what they said it was,” he says.

Hariri says he won’t recommend overseas clinics to his patients, but doesn’t discourage them from doing their own research and deciding to visit one. “People make choices today on what restaurant they go to, what doctor they go to, which hair clinic they go to, based upon what other people’s experiences are,” he says. According to Diamandis, Fountain Life (of which he and Hariri are founders) does recommend its members to the Regenerative Medicine Institute in Costa Rica for stem cell treatments.

Hariri, Diamandis, and Robbins all say they advocate clinical trials in the U.S. Fountain Life and Cellularity are pursuing FDA approval to start trials at a facility in Florida this year. Hariri is aiming to have FDA-worthy test results by 2026.

Reprogramming Cells with Epigenetics

Why get young cells from other people if you can return your own cells to their youthful vigor? That’s the promise of epigenetic reprogramming.

“All kinds of different cell types originate from one cell originally,” says Shelly Berger of U Penn. “So, the turning on of certain genes to lead to a brain cell or a skin cell or a liver cell is important…And so you can imagine that the loss of that information, when it goes awry, could lead to some big, big problems.”

People talk colloquially about turning genes “off” or “on.” But what’s really happening is winding up or unwinding strands of DNA. Some enzymes in the cell wind genes into spools, known as chromatin, blocking RNA molecules from reading the instructions for producing proteins. Other chemicals unspool the chromatin, making the genes readable. (This isn’t the only component of epigenetics, but it’s a key part.)

Pollution, radiation, bad diet, lack of exercise, and other stressors can damage both DNA and epigenetic mechanisms. Shelly Berger and colleagues are studying a therapy for nerve cells, using an unspooling enzyme called Acetyl Co A synthetase. “That leads to turning on genes that are involved in learning and memory and creating new circuitry in the brain,” she says.

Another take on renewing the epigenome is getting the most hype—and money. And it has a link to stem cells. In 2012, Shinya Yamanaka won the Nobel Prize for developing a way to convert an adult cell—one specialized for brain, muscle, or bone—back into an “undifferentiated” cell, which can turn into anything. These “induced pluripotent” stem cells, are one arm of stem cell therapies. Yamanaka discovered (and lent his name to) four proteins, called transcription factors, that drive this transformation.

In 2016, researchers at the Salk Institute announced that the right mix of Yamanaka factors, administered in the right cadence, could take the process just partway. It converts a cell not back to its undifferentiated form but just back to a younger version, with a youthful epigenome.

They demonstrated these results in whole mice, as well as samples of human cells, which both showed reversal of many aspects of aging. The work was led by Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte—who would go on to play a major role in the multibillion-dollar antiaging crusade.

But the biggest name in cellular reprogramming is David Sinclair. While many proponents speak haltingly about reversing aging—rather than just slowing it—Sinclair and his team are unambiguous. “Our work has led us to identify reprogramming factors that we believe will enable us to reset a cell’s epigenetic status and reverse its age,” reads the Sinclair Lab website. (Sinclair declined an interview but did answer questions over email.) That philosophy is right in the title of his 2019 bestselling book, Lifespan: Why We Age – and Why We Don’t Have To.

(In January 2023, Brenner published “A Science-Based Review” of Lifespan and the accompanying podcast. It reiterates his Twitter critique of the sirtuin and resveratrol theories, and adds warnings about epigenetic reprogramming.)

In 2020, Sinclair and a gaggle of researchers published a paper claiming to have improved vision in mice suffering from glaucoma, using Yamanaka factors to give damaged optic nerve cells regenerative ability. They claimed similar results in individual human cells. “That’s a nice paper,” says Shelly Berger, who was not involved in it.

But the blockbuster came in a collaborative study from January 2023 (which included Berger). Many news articles about the study feature a side-by-side photo of treated and untreated twin mice—one grizzled and gray, one bushy and ebony. A CNN article alluded to Benjamin Button. An interview with Sinclair in the Harvard Gazette was titled, “Has the first person to live to be 150 been born?”

Delivering Yamanaka factors is tough. It requires loading them into viruses that then infect the cells. But a Sinclair collaboration reported last July that “cocktails” of much simpler substances, called small molecules, can imitate what Yamanaka factors do. “This new discovery offers the potential to reverse aging with a single pill,” wrote Sinclair, in July, on what was still called Twitter.

No surprise: Charles Brenner is skeptical. It starts with the dangers in the older process of using Yamanaka factors to create stem cells. “You have to realize, the vast majority of the treated cells either die or go down some very undesirable lineage,” he says, “including teratomas, and malignancies.” Malignancy is spreadable cancer; teratomas are freakish growths in which the wrong kind of cells grow in the wrong places. Imagine hair and teeth growing in your pelvis. (That’s a real-life human case, though not associated with cellular reprogramming.)

Numerous reprograming studies either explicitly say that cancer didn’t occur or don’t mention it as a result. Sinclair says that a reprogramming study from 2020 didn’t find elevated rates of cancer in mice. But that’s not proof enough for Brenner. “I don’t think that healthy humans will ever be enrolled in an ethical clinical trial of Yamanaka factors, because the risk of cancer will be too great,” he says.

Kaeberlein agrees that cancer is a concern but is also cautiously optimistic. “Conceptually, given how it works, and what’s been done so far…it’s possible that we could get to the point where we’re talking about doubling, or even more, the healthy lifespan of a mammal—of a mouse, for example, and maybe someday in people,” he says.

But he’s not impressed by the current evidence and says that the tests of the reprogramming “cocktails” provided only preliminary indication that they might work. “Here’s where the hype has gotten ahead of the reality,” he says. “And unfortunately, this has been intentionally presented in a dishonest way, I believe.”

Though lesser-known than Sinclair, Izpisua Belmonte, of the original 2016 reprogramming study, is emerging as one of the most-powerful players in antiaging. In 2022, he launched reprogramming company Altos Labs, which has attracted about $3 billion in funding from Silicon Valley captains. It’s also attracted top talent—such as Morgan Levine, formerly of Yale, and Steve Horvath, formerly of UCLA, who have developed (controversial) methods for measuring cellular aging. “There may be some hype, but it’s taken very seriously,” says Berger. “There’s a lot of work being done, and Altos is serious.”

Altos is the biggest, but not the only, massively funded antiaging company. Others include Retro Biosciences, which is working on cellular reprogramming as well as other technologies and has raised $180 million, according to Crunchbase; and drug-discovery company Recursion Pharmaceuticals, which has attracted over $665 million. David Sinclair is a cofounder of Life Biosciences, which works on epigenetic reprogramming and has been funded to $206.8 million.

Such companies and their backers most inspire the trope of the crazy billionaire who wants to live forever. While several billionaires (and other very wealthy people) are backing the antiaging movement, technologies like epigenetic reprogramming are far too nascent to conclude whether or not these supporters are crazy.

Fountain of Youth, or Fount of BS?

If you’d hoped for a conclusive destination at the end of this journey, I’m sorry. But in place of answers, we have a framework for evaluating the many questions that emerge. Science has a good sense of what healthy aging should look like. And objective research can begin to explore if any far-fetched ideas mimic that, without bad side effects.

What the spectrum of players agrees on—from Charles Brenner to David Sinclair to Tony Robbins—is that we already know many ways to combat aging. Do better eating, sleeping, exercising, and just living a full life.

Can “eating” extend to swallowing supplements that boost cell health? It seems likely with some pills—but not nearly as many as are hyped in social media, podcasts, and a Google search. Can healthy diet extend to eating less or on weird schedules? Possibly.

Some medications might slow down some aspects of aging. Or perhaps the side effects of these meds just substitute new health problems for the ones proponents aim to fix. You might wait for more info on that before you swallow.

Can we inject foreign cells to repair our bodies or inject chemicals that reinvigorate our own cells? This seems to work in mice, worms, or petri dishes. But people without vested interests say we need much more evidence. That’s going to take a long time.

Can you trust supplement advice from someone whose company sells supplements? Are they promoting therapies to promote their business, or vice versa? Or both? Would you trust medical advice from a motivational speaker? But what conflicts does even a university scientist, with a commercial side business, suffer? Consider not just what people are saying, but why they might be saying it. Perhaps it’s deception, or just wishful thinking.

For so much of antiaging or reverse-aging science, the old academic refrain applies: “further research is needed.”

Until—or if—better evidence emerges, anyone can goose their chances for living longer and better by maintaining a healthy lifestyle. That might be the first step in reaching escape velocity to a fantastically long life. But even if not, it helps you make the best of whatever life nature affords you.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misnamed the substance NMN as “NMH.” It also stated that four companies Charles Brenner is involved in relate to NR.