One of California’s marquee programs for cleaning up transportation emissions is at a crossroads. Decisions made in the next few months could set the decade-and-a-half-old Low Carbon Fuel Standard on one of two very different paths.

One path, favored by fossil fuel and renewable natural gas interests, would lock in a market scheme that currently extracts billions of dollars per year from Californians at the pump and subsidizes crop-based and cow-manure-derived biofuels.

That would be a disaster, according to environmental advocates, who point to a growing body of scientific evidence showing that this approach, if extended until 2045 as proposed, would cause these biofuels to grow at a scale that would harm the climate and the environment.

The other path, proposed by environmental groups, transportation-decarbonization analysts and climate and energy researchers, would limit the scope of unsustainable biofuels in the program, and instead reorient it to support what experts agree should be California’s primary clean transportation pathway: electric vehicles.

To date, roughly 80% of LCFS funding has gone to combustion biofuels rather than electric vehicles. That’s simply incompatible with the state’s EV ambitions and needs, said Adrian Martinez, deputy managing attorney of nonprofit advocacy group Earthjustice—and the imperative to reduce emissions from transportation, which account for nearly 40% of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions.

“We’ve got to eliminate our reliance on combustion,” he said, but “the program as designed will continue to provide lucrative incentives for combustible fuels well into the future.”

The regulator in charge of the LCFS program—and this high-stakes decision—is the California Air Resources Board. CARB’s board, which comprises 14 voting members, 12 appointed by the governor and two by the state legislature, holds a host of responsibilities around California’s energy transition. Those include shaping the state’s nation-leading EV policy, as well as determining its broad plans for achieving long-term greenhouse-gas reduction goals.

Critics say the LCFS program’s increasing support for biofuels is in direct contrast to both the EV targets and the climate goals also overseen by CARB—and that the program has been captured by deep-pocketed industries trying to greenwash the continued use of combustion fuels.

CARB has a chance to reform the program with an upcoming vote, initially set for this month, but now postponed to an undetermined future date. But its pathway to fixing the problems that plague LCFS is murky and messy at best.

Right now, the staff managing the LCFS program hasn’t given CARB board members an opportunity to pick a climate- and EV-friendly alternative. Instead, a December staff proposal provides only one option for the board to vote on later this year: a set of policies that Earthjustice forecasts would direct $27 billion over the coming decade toward biofuels and worsen effects on the climate, the environment and the prices that Californians pay at the pump.

CARB does have another option, however—an alternative proposal laid out by CARB’s Environmental Justice Advisory Committee, created to advise the board on environmental-justice issues.

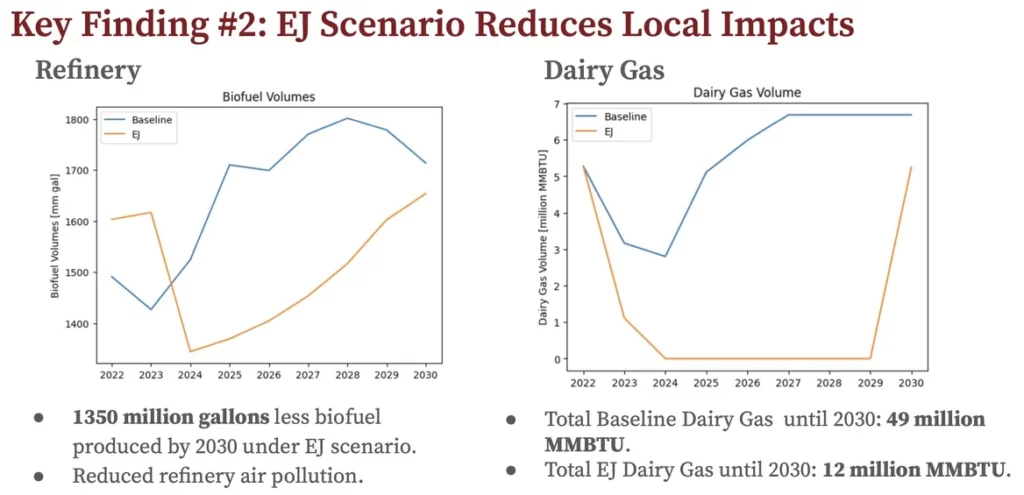

That proposal would cap the fast-growing share of crop-based renewable diesel flooding the state. It would also end the unusual structure that now allows biogas produced by dairy farm manure to offset a much higher amount of carbon emissions than any other source of alternative fuels.

And, importantly, it would make the core of the program—its carbon-offset marketplace—function in a much healthier way, proponents say. A torrent of cheap, polluting renewable diesel and dairy farm biogas credits have dragged down the price that LCFS credits can fetch for avoiding emissions, diluting the incentive to deploy new climate technologies and sapping what could be a key funding source for EV infrastructure in the state.

“The stakes are very, very high,” Martinez said. “That’s why you see so much attention focused on this—and a very broad and diverse coalition that is pushing for more systemic change to the program, versus more modest tweaks that will really just keep this market owned and dominated by fossil fuel interests.”

A History of the LCFS Program

California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard was born out of AB 32, the 2006 law that created the state’s carbon cap-and-trade market. Much like carbon markets, LCFS is meant to make companies pay for their carbon emissions by buying credits from technologies that reduce carbon emissions.

The program requires all fossil fuels refined and sold in California to meet increasingly stringent carbon-intensity targets. In practice, fossil fuel producers have to buy a bunch of LCFS credits from low-carbon transit sources operating in the state in order to comply. The goal is to create a system that taxes planet-warming fossil fuels to fund cleaner transportation alternatives.

But the LCFS has strayed from its initial focus on vehicle electrification and “advanced” non-crop-based biofuels to become “a swag bag for venture capitalists, big oil, big agriculture, and big gas, increasingly coming at the expense of low- and moderate-income Californians.” That’s how Jim Duffy, a 13-year veteran of the agency who served as branch chief of the LCFS program from 2019 to 2020 and retired in 2022, described the evolution of the program in comments filed with CARB.

Under the LCFS regulation adopted in 2009, dairy-manure-to-biogas projects did not receive special treatment compared to other sources of methane such as landfills and sewage treatment plants, Duffy wrote. Similarly, diesel fuels made from crops like soybeans were considered “only marginally better than fossil diesel.”

But in the years since, “the LCFS was revised to provide additional and unnecessary support to landfills and first-generation crop-based biofuels” and “to mitigate the methane problem created by the dairy industry itself,” Duffy wrote—despite the fact that evidence increasingly suggests that both sources harm the planet far more than they benefit it.

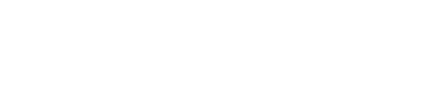

The result has been an increasing share of LCFS credits being supplied by renewable diesel and dairy-generated biogas.

CARB has justified these shifts with analysis indicating they will yield net positive climate impacts.

“The proposed amendments now under consideration will directly increase the program benefits in the most burdened communities, by reducing the carbon across the supply chain for fuels sold in California, as well as improving public health for fuels sold in California,” CARB spokesperson Dave Clegern said in an email to Canary Media. He cited data from CARB staff’s analysis of its proposal indicating that, by 2045, its plan will reduce nitrogen oxide emissions by 25,586 tons, cut greenhouse gas emissions by 560 million metric tons and yield public-health cost savings of nearly $5 billion.

But critics say the agency is failing to account for the full scope of climate harms that will be caused by its continued emphasis on biofuels.

They warn that the sheer scale of California’s program — totaling some $4 billion per year — is driving investment in the wrong transportation alternatives. The consequences are dire, they say — not just within the state, but across the country and around the world.

Why Renewable Diesel Is Threatening CARB’s Climate and Credit Goals

Take renewable diesel, a fuel made from fats and oils processed to be identical to fossil diesel fuel. The U.S. increased production of the fuel by 400% between 2019 and 2022, and it is set to double it again this year, according to Jeremy Martin, senior scientist and director of fuels policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists.

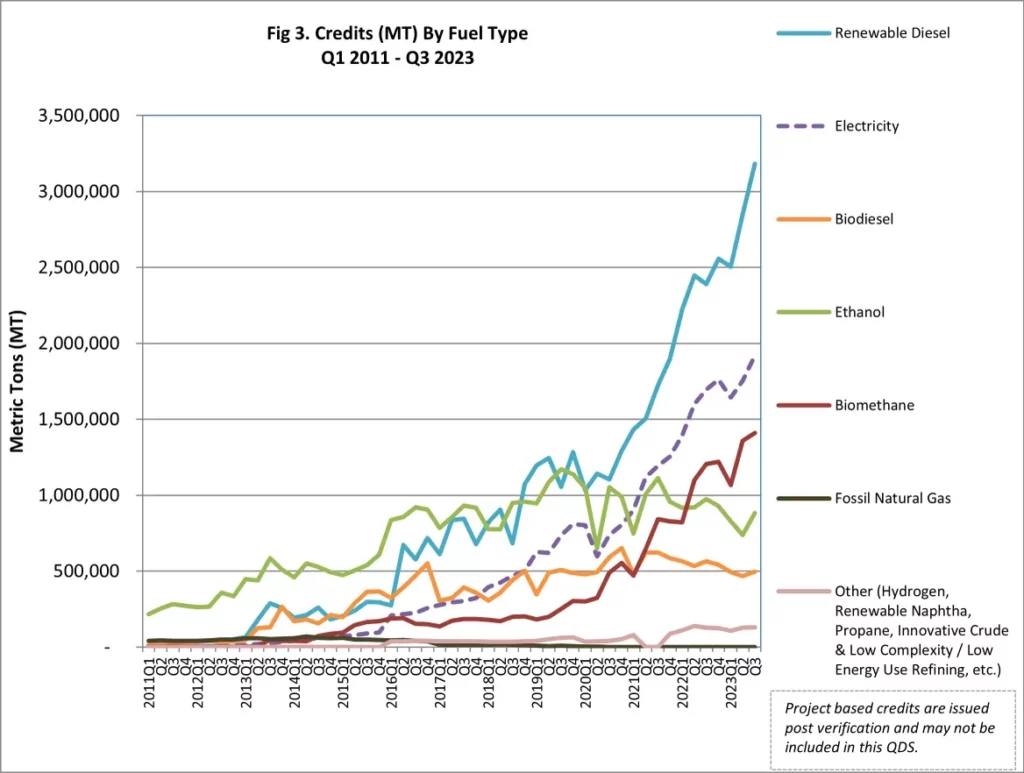

Unlike ethanol and biodiesel, which can only partially replace gasoline and diesel, renewable diesel has “no limit on how much can be blended,” Martin said. It could theoretically completely replace diesel fuel for trucks, buses and other vehicles. And California’s LCFS offers credits on top of the federal incentives the fuel receives, making the state the primary target of renewable diesel producers across the country.

As a result, the share of renewable diesel as a percentage of total diesel fuel use has skyrocketed in California compared to the rest of the U.S., as the chart below shows.

In a September meeting, Steven Cliff, CARB’s executive officer, highlighted a milestone for the LCFS program: As of mid-2023, California had “more than half of our diesel demand being met by non-petroleum-based diesel alternatives. This is a direct result of the LCFS program, and it’s bringing real climate and air-quality benefits to the state.”

In Martin’s view, that milestone is not a win, but a warning. It indicates that renewable diesel is “flooding the LCFS, drowning the policy—and it doesn’t make sense” on climate or environmental terms.

Once the demand for renewable diesel outgrows the supply of waste oils and other non-crop feedstocks that can be used to make the fuel in genuinely climate-friendly ways, it becomes highly likely that it will cause more greenhouse gas emissions than it will displace. Critics like Martin argue that demand has now reached this point, though it’s a contested question.

This additional demand for crop oils could mostly serve “to expand the cultivation of palm oil to replace the soybean and other oils made into fuel,” the Union of Concerned Scientists argued in comments to CARB. That, in turn, is likely to lead to more rapid deforestation in nations that produce large amounts of these crops, such as Brazil and Indonesia—an outcome that would cause far greater climate harms than whatever emissions reductions result from replacing fossil diesel.

To stop this, the Union of Concerned Scientists and other groups want CARB to set a limit on how much renewable diesel can receive LCFS credits. CARB staff’s proposal declines to set such a cap, citing renewable diesel’s climate and health benefits.

To stop this, the Union of Concerned Scientists and other groups want CARB to set a limit on how much renewable diesel can receive LCFS credits. CARB staff’s proposal declines to set such a cap, citing renewable diesel’s climate and health benefits.

But CARB’s methodology is out of step with the latest science, according to multiple groups studying these issues. The Union of Concerned Scientists, for its part, says CARB’s analysis is “based on inaccurate claims of climate and air-quality benefits and associated health outcomes.”

In a recent comparison of five different models for evaluating the climate impacts of crop-based biofuels, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency found that only CARB’s own model shows a positive carbon-reduction impact.

And while the agency has a proposal to limit deforestation harms by setting “sustainability guidelines” for crops being used for renewable diesel, it applies only to feedstocks grown in the U.S., Martin noted. That’s a problem: California is on pace to consume 10% of global soybean oil supplies for renewable diesel, meaning a significant amount of the crop oil produced for the program will be grown under conditions CARB cannot police, he said.

Given that reality, Martin said, “If California declines to act—if they say, ‘This is evidence of success; look how little fossil diesel we’re using’” by replacing it with renewable diesel, “then, in fact, California is giving its support to a fuel that we know is unsustainable at these volumes.”

The Risks of Tilting California’s Biomethane Credits to Reward Dairy Farms

Environmental groups have similar concerns with how the LCFS makes methane captured from dairy farms—an important and politically powerful industry in the state—much more lucrative than any other source of biofuel.

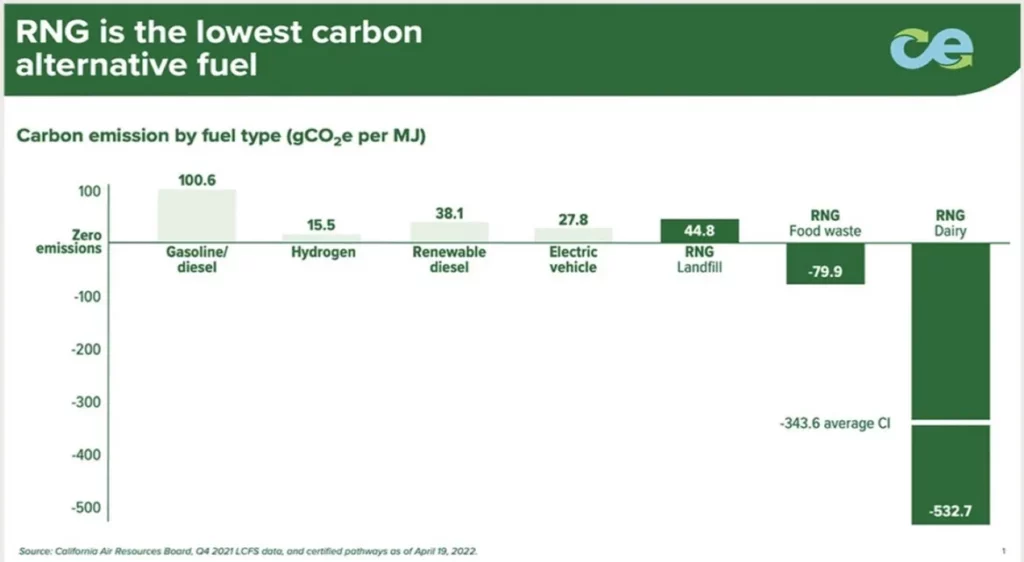

In 2018, CARB altered its “carbon-intensity” accounting of dairy farm methane, also known as renewable natural gas (RNG). This methane is captured from lagoons of cow manure and converted to RNG in facilities known as “digesters.” That gas can be burned on-site to generate electricity, compressed for use as a vehicle fuel or injected into fossil gas pipelines. As a result, every unit of methane captured from a dairy farm is assumed to have a “negative carbon-intensity” impact that LCFS credit buyers can use to erase emissions deficits from a much larger amount of fossil fuels.

That has allowed a source of biogas that makes up less than 1% of the fuel energy used in the state to receive almost 20% of the credits in the LCFS program, according to Earthjustice comments to CARB.

“Livestock methane significantly dilutes the supply of LCFS credits relative to the actual fossil fuel displaced,” pulling investment away from more effective decarbonization tools like EVs, the group argued.

According to CARB staff, this generous treatment of dairy biogas is necessary to give dairy farms the financial incentives to invest in methane capture and treatment equipment, without which they would emit even more of the global warming gas.

“Whether we do it with federal incentives, state standards, the LCFS or direct regulation, what’s going to happen to control these emissions is digesters,” Rajinder Sahota, CARB deputy executive officer for climate change and research, said at CARB’s September meeting on LCFS.

But critics say the more useful approach to solving this climate problem is for CARB to actually enforce a 2016 state law that mandates California slash methane emissions by 2030. Environmental groups are calling on CARB to set penalties for dairies that fail to reduce their methane emissions under that law. To date, CARB has no such plans.

As Duffy wrote in his CARB comments, “No other industry is treated as if their methane pollution is naturally part of the baseline and then lavished with large financial incentives for simply reducing their own pollution”—certainly not oil companies or landfill operators, which are instead “regulated and penalized for their emissions.”

CARB’s treatment of dairy farm methane digesters has made them lucrative for oil companies. In the past two years, oil majors including BP, Chevron and Shell have invested billions of dollars in U.S. biogas production, most either selling their biogas in California or using the LCFS program’s lax accounting structures to claim LCFS credits for biogas generated outside the state.

“It is no wonder that oil companies are investing heavily in dairy digesters, as it allows them to comply with the LCFS, make a profit doing so, and retain their market share for fossil fuels,” Duffy wrote.

The LCFS Market Is Broken

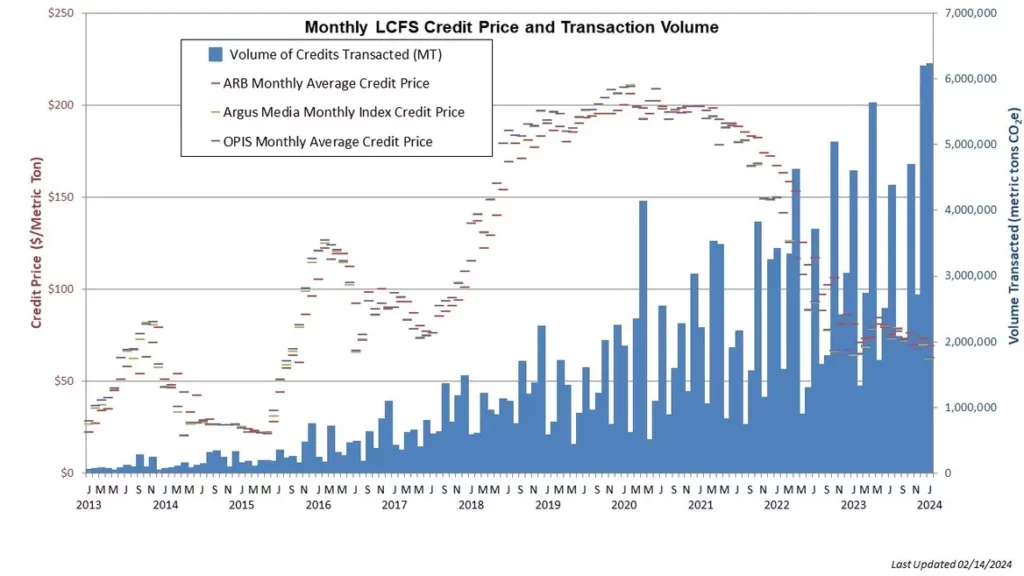

All of these disputes are taking place against the backdrop of a pressing concern at CARB: finding a way to reverse the crash in LCFS credit prices that’s occurred over the past few years. Those prices have fallen from about $200 per ton of abated carbon in 2020 to between $60 and $70 per ton in 2023, reducing the amount of funds being transferred from fossil fuel producers to providers of alternative technologies—a category that includes not just biofuels, but also a range of credits available for lowering the cost of EV purchases and EV charging deployments.

CARB staff proposes to tackle this by tightening the carbon-intensity targets for fossil fuels—essentially increasing the amount of alternative lower-carbon fuel credits they must acquire to balance out emissions deficits for each unit of fossil fuel sold in the state—which will increase the amount of credits fossil fuel refiners and sellers need to purchase. This approach has won the support of developers of biofuels and biogas, as well as the Western States Petroleum Association, an oil and gas trade group that was in the top three largest spenders in lobbying California lawmakers last year.

But environmental groups and climate scientists argue that this approach fails to tackle the biggest problem with LCFS: the oversupply of credits coming from renewable diesel and dairy biogas, which in their view don’t actually help combat climate change. It also creates the risk of driving up prices at the pump, which could harm budget-constrained drivers and spark public outcry.

By contrast, slowing down the growth of renewable diesel and dairy biogas will reduce the environmental harms the program causes and redirect it toward sourcing credits from a smaller, more effective range of alternative fuels, environmental groups argue. That will increase the price those credits can command in the market without running the risk of flooding it with excessive credits of dubious value, they say.

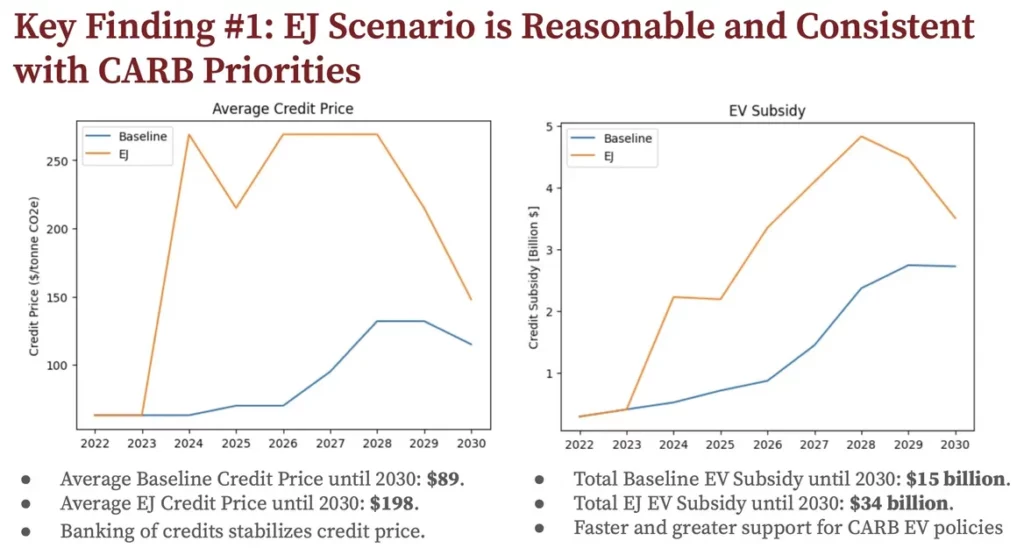

That’s the strategy that CARB’s Environmental Justice Advisory Committee (EJAC) provided to CARB in a September workshop, based on analysis from a team of climate scientists led by Michael Wara, director of Stanford University’s Climate and Energy Policy Program.

That analysis found that the EJAC proposal—which centers on capping renewable diesel and ending the avoided-methane treatment of dairy biogas—would not only reduce harmful local pollution more than the CARB staff proposal but also increase average LCFS credit prices and the amount of subsidies going to EVs and EV charging.

But CARB staff’s December proposal for revising the LCFS program did not offer this EJAC proposal as an alternative option for the CARB board to consider. Instead, the staff’s proposal reviewed and dismissed it as unviable, asserting that it would cause LCFS prices to spike far higher than the EJAC analysis indicated while failing to achieve equivalent carbon reductions.

Wara and colleagues involved in the EJAC analysis challenged that finding in comments submitted to CARB in February. They highlighted what they described as multiple flaws in the CARB staff’s proposal, as well as the “lack of transparency” in its analysis of the EJAC proposal.

They also warned that CARB’s pending decision on the LCFS program could “lock in a variety of large subsidies for particular technologies” that “are being offered to extremely powerful industries in California. Once offered, they will be exceedingly difficult—both from a practical and a political perspective—to pull them back as circumstances evolve.”

Getting the EV Industry the Money it Needs

Far better, environmental-justice groups contend, would be to redirect the LCFS program to serve the state’s most promising and practical “zero-emissions pathways”—namely, electric vehicles and public transit. Unfortunately, the LCFS program is currently falling short on that front, said Nikita Pavlenko, fuel program lead at the nonprofit research group International Council on Clean Transportation.

Pavlenko highlighted several ways that low LCFS credit prices are stifling the program’s ability to support state EV policies. One example is the state’s Clean Fuel Reward program, a joint effort between CARB and California’s three major utilities.

Today, utilities set aside a portion of the LCFS credits they earn for electricity sales for residential EV chargers to fund rebates to encourage consumers to buy EVs, he said. That allowed the program to deliver $319 million in rebates from its November 2020 launch to May 2022—20% of that to customers in underserved communities, according to CARB.

But the drop in LCFS credit prices has starved that program of funds. As a result, the $750 rebates the program once offered have been “temporarily reduced to $0,” as the program’s website states, a change driven both by “higher than estimated growth of electric vehicle sales in California” and “[l]ess revenue than initially estimated from the sale of LCFS credits.”

High and stable LCFS credit prices are even more important for the state’s Advanced Clean Fleets rule, a policy enacted by CARB last year that mandates the decarbonization of the state’s 1.8 million commercial trucks over the next two decades. CARB’s analysis of the rule found that the state’s trucking industry could cost-effectively convert its fleets to battery electric vehicles, partly by allowing electric-truck charging providers to apply the value of LCFS credits they receive for the electricity they sell so they can reduce the price they charge for it.

But that analysis assumed that LCFS credit prices would remain in the $200 range, and that these funds would be available to help pay for the cost of deploying the hundreds of megawatts of heavy-duty EV charging required to support the shift to electric trucks. Today’s much lower LCFS credit prices seriously erode those economics, said Adam Browning, executive vice president of communications at Forum Mobility, an electric truck charging and leasing provider.

An analysis by the startup found that the difference between LCFS credits in the $200 range that CARB is targeting and the $70 range they’re now selling for “translates to about $1,000 a month in increased fuel costs” per truck, he said. Drayage trucks hauling cargo from the state’s ports to inland distribution centers spend between $3,000 and $5,000 per month on diesel fuel, he noted. In that context, “$1,000 a month from LCFS is a really big deal.”

“LCFS is a crucial program, and it has the ability…to drive no less than the success or failure of the overall transition to zero-emissions vehicles,” Browning said. “It’s just about making appropriate choices.”

But right now, Earthjustice’s Adrian Martinez said, CARB’s choices around transportation electrification and its LCFS program appear to be working at cross purposes. “At one end of the agency, they’re doing incredible work to pass regulations for zero-emissions trucks,” he said. “And on this end, there’s really this legacy anchor of combustion that’s dragging us down.”